The easiest person to fool is yourself. Thus spake one of the greatest minds to visit this planet, Richard Feynman, someone who was rarely anyone's fool.

He certainly would have seen through a youthful enthusiasm that I had. Following University, and exploring many of those things I had not had the time for while immersing myself in biology, I ventured into the musty and old fashioned halls of my local library and scoured the shelves. I picked up many modern physics volumes by the likes of Paul Davies and John Gribbin. I read fiction, from Lawrence Durrell's impenetrable novels, to Virginia Woolf's interior monologues to Thomas Hardy and beyond. I absorbed like a sponge, widening my education as widely as I could.

One day I came across a volume that intrigued. It was Shakespeare Identified by J Thomas Looney (1920) and I duly took it home, read it and wondered whether it might be true or not. Here was an interesting little non-scientific conundrum that might be solved in a scientific style. As presented by Looney, the hypothesis that William Shakespeare (1564-1616) did not write the plays and poems that are associated with that name, rather that they were written by Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550-1604), had some attractions. It looked interesting rather than plausible. After all, de Vere died well before the last of Shakespeare's plays, The Tempest, which was based on contemporary events, sort of.

Edward de Vere (above) had one favourable point in all this so far as I was concerned. He was a man of Essex, my home county, so to be able to claim the world's greatest dramatist as a man from the soil of Castle Hedingham in Essex was worthwhile pursuing. I had been singularly unimpressed trotting around Stratford Upon Avon a few years before and felt that perhaps Stratford, East London (Essex to me) was the place where this particular swan might have swum.

And de Vere did write, and leave some poems behind for our delectation. I wasn't much struck by them but Looney was, and he made a case based on some biographical points about de Vere, his decidedly worthy sounding poems and not a lot else. I caricature the argument because in the end it is based on personal incredulity: how could someone so untutored (Shakespeare didn't even go to University, either of them) produce such stunning works, immortal and never bettered. How dare he? He had little Latin and less Greek, according to his contemporary Ben Johnson, so how did he do what he did?

Simple really. Shakespeare is full of silly mistakes that someone with more learning probably wouldn't have made. His is book learning, and we know with a degree of certainty the books that inspired or served as models for some of the plays, especially the history plays. But he only needed to be intelligent, a keen learner and a good observer to have worked out deeper truths than his contemporaries ever managed. And there have been many clever people who made gigantic mistakes.

E A J Honnigman's Shakespeare The Lost Years (1985) makes some claims about what happened between the young playwright leaving school and arriving, fully formed, in London's theatre land. He may or may not have been a Catholic, but he probably was getting a deeper education, in a stately home in Lancashire. This book opened my eyes to the fact that learning for Shakespeare did not begin and end with a grammar school education of his day but continued through his life.

Looney was just plain wrong on the authorship question. There really isn't one. And when I had settled that answer in my mind, I reread his book and saw all the flaws that had lain hidden in the exciting first flush of the idea. Looney had fooled himself and looked harder and harder for things that just weren't there. Conspiracies do happen, of course, but they are hard to hide and harder to execute with complete secrecy. Easier just to accept that the simpler hypothesis is true: a man from the Midlands wrote some of the greatest literature ever, and he didn't have to go to Cambridge to learn how to do it. He certainly didn't have to cheat death (Marlowe) and do it while simultaneously pursuing a career as a full time philosopher and scientist (Bacon).

Just because Looney could not believe Shakespeare was the author does not make Looney right. But he impressively marshalled a huge pile of evidence that I did not know about, just as Darwin did. The difference is that Looney had to strain his evidence to breaking point. Darwin was content to pile his up, knowing that each additional fact bolstered his argument. It matters little that there isn't much of a paper trail to Shakespeare's life: when researching for my wife BA dissertation, we chased down a number of individuals, including the twice lord mayor of London and immensely rich merchant John Hende (admittedly two hundred years before Shakespeare). Hende appears mostly as a regular attender in court, usually on some money matter. He has no real outside existence and is a shadowy figure compared to his more famous contemporary, Richard Whittington. If we look at Shakespeare as Hende and de Vere as Whittington, we get an idea of how they really were. De Vere, after all, spent much time at the Court of Elizabeth I. Shakespeare was a jobbing actor and a playwright. The latter job isn't done in the limelight.

Back to what Feynman said. As I read Looney's first book, its sequel and those thick, lumpy volumes of his supporters, the sheer mass of evidence made the hypothesis seem convincing. But when I checked the facts, they dissolved one by one. Stratfordians, as they are rather insultingly labelled, back the traditional horse: Shakespeare was Shakespeare. And they hold all the aces. They don't have to argue about funny dates for the last few plays, or the first few, or whatever. They hold those aces because the original attribution is correct. We will learn more about Shakespeare as time goes by. Somewhere there must be more documents waiting to be uncovered, or scraps wrongly archived, that will give us just a tiny bit more of a biography of the Stratford, Warwickshire man. But the emotional pull of the Essex man was momentarily strong.

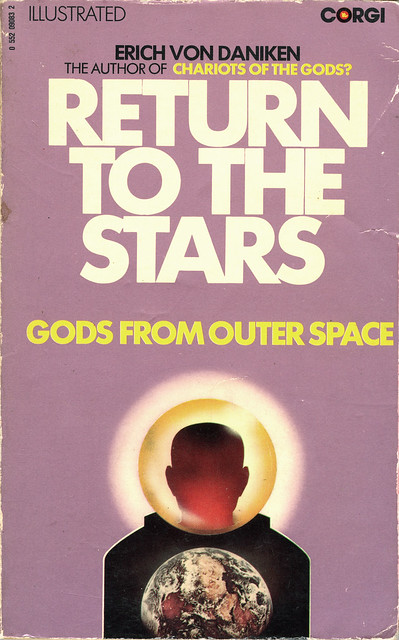

And wrong. I wanted de Vere to be the author that it tainted my thinking for a couple of months. It was just as it was when I read Erich von Daniken when I was at school (second year, now year 8, silent reading on a Friday morning - I was reading Return To The Stars) and thought there might be something in this. Well, I was wrong. I didn't know enough, and was impressionable, to realise that every if... was not a fact but a conjecture and that if it became a "fact" a few lines further on, it wasn't any more correct than it had been earlier. But as I learned more, I came to realise that pseudo-archaeology like this isn't good science at all. It is rubbish, corrosive pseudoscience. And it hides the deeper truths. We may have had alien visitations but this book and ones like it don't prove it. Not even close. But at 12 the idea was dynamite and I dearly wanted it to be true.

By checking these ideas against other books, or my own observations, I came to a deeper understanding. Quite often, the truth is dull, but it is only dull because it is the truth. Ideas can be true and exciting: evolution, relativity, quantum electrodynamics are all exciting and true and to many a mind can be dull. But how dull is it that all living things on the planet are connected at the deepest level of chemical reactions, or that gravity and mass are imperfect bedfellows, dancing around in space-time...

Einstein, of course, fooled himself into fiddling his equations to make a static universe because that's what he thought was the case. When it was discovered that the Universe was expanding, he was embarrassed. Who wouldn't be? But science is capable of accepting its mistakes and moving on from them. Still squabbling over the Shakespeare authorship question, Oxfordians have had the recent boost of a posh, expensive and downright wrong film, Anonymous, backed by such luminaries as (personal hero since I Claudius) Derek Jacobi. Science teaches that experts are only experts if the evidence backs them up. Sorry, Sir Derek, the evidence doesn't back the Oxford case. Edward de Vere, dilletante, bit time poet, forgotten playwright, part time warrior, courtier to Elizabeth I, isn't Shakespeare.

"The easiest person to fool is yourself."

ReplyDeleteYou've done a great job of it.

"I wanted de Vere to be the author that it tainted my thinking for a couple of months. It was just as it was when I read Erich von Daniken when I was at school (second year, now year 8, silent reading on a Friday morning."

How charming. When are you going to grow up and realize that making the same choice twice doesn't make you smart. It just makes you boring.

"By checking these ideas against other books, or my own observations, I came to a deeper understanding."

Do you hear how pompously abstract you sound? What ideas? What other books? O, you just want us to trust you. Sorry, this reader doesn't trust you at all. You sound like a person who is so concerned with being on the "correct" side that you've completely forgotten how to apply any authentic critical thinking. You go through the motions, but it ain't the same thing.

I am sorry I failed to reach the ideals you hold. I realised I was being dragged along not by the evidence but by the excitement of potential heresy. I have little doubt that many have felt that excitement in the course of 2016. As for wanting to be on the right side, I was young and callow then, I'm older than that now.

DeleteI try to apply authentic critical thinking now