The easiest person to fool is yourself. Thus spake one of the greatest minds to visit this planet, Richard Feynman, someone who was rarely anyone's fool.

He certainly would have seen through a youthful enthusiasm that I had. Following University, and exploring many of those things I had not had the time for while immersing myself in biology, I ventured into the musty and old fashioned halls of my local library and scoured the shelves. I picked up many modern physics volumes by the likes of Paul Davies and John Gribbin. I read fiction, from Lawrence Durrell's impenetrable novels, to Virginia Woolf's interior monologues to Thomas Hardy and beyond. I absorbed like a sponge, widening my education as widely as I could.

One day I came across a volume that intrigued. It was Shakespeare Identified by J Thomas Looney (1920) and I duly took it home, read it and wondered whether it might be true or not. Here was an interesting little non-scientific conundrum that might be solved in a scientific style. As presented by Looney, the hypothesis that William Shakespeare (1564-1616) did not write the plays and poems that are associated with that name, rather that they were written by Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550-1604), had some attractions. It looked interesting rather than plausible. After all, de Vere died well before the last of Shakespeare's plays, The Tempest, which was based on contemporary events, sort of.

Edward de Vere (above) had one favourable point in all this so far as I was concerned. He was a man of Essex, my home county, so to be able to claim the world's greatest dramatist as a man from the soil of Castle Hedingham in Essex was worthwhile pursuing. I had been singularly unimpressed trotting around Stratford Upon Avon a few years before and felt that perhaps Stratford, East London (Essex to me) was the place where this particular swan might have swum.

And de Vere did write, and leave some poems behind for our delectation. I wasn't much struck by them but Looney was, and he made a case based on some biographical points about de Vere, his decidedly worthy sounding poems and not a lot else. I caricature the argument because in the end it is based on personal incredulity: how could someone so untutored (Shakespeare didn't even go to University, either of them) produce such stunning works, immortal and never bettered. How dare he? He had little Latin and less Greek, according to his contemporary Ben Johnson, so how did he do what he did?

Simple really. Shakespeare is full of silly mistakes that someone with more learning probably wouldn't have made. His is book learning, and we know with a degree of certainty the books that inspired or served as models for some of the plays, especially the history plays. But he only needed to be intelligent, a keen learner and a good observer to have worked out deeper truths than his contemporaries ever managed. And there have been many clever people who made gigantic mistakes.

E A J Honnigman's Shakespeare The Lost Years (1985) makes some claims about what happened between the young playwright leaving school and arriving, fully formed, in London's theatre land. He may or may not have been a Catholic, but he probably was getting a deeper education, in a stately home in Lancashire. This book opened my eyes to the fact that learning for Shakespeare did not begin and end with a grammar school education of his day but continued through his life.

Looney was just plain wrong on the authorship question. There really isn't one. And when I had settled that answer in my mind, I reread his book and saw all the flaws that had lain hidden in the exciting first flush of the idea. Looney had fooled himself and looked harder and harder for things that just weren't there. Conspiracies do happen, of course, but they are hard to hide and harder to execute with complete secrecy. Easier just to accept that the simpler hypothesis is true: a man from the Midlands wrote some of the greatest literature ever, and he didn't have to go to Cambridge to learn how to do it. He certainly didn't have to cheat death (Marlowe) and do it while simultaneously pursuing a career as a full time philosopher and scientist (Bacon).

Just because Looney could not believe Shakespeare was the author does not make Looney right. But he impressively marshalled a huge pile of evidence that I did not know about, just as Darwin did. The difference is that Looney had to strain his evidence to breaking point. Darwin was content to pile his up, knowing that each additional fact bolstered his argument. It matters little that there isn't much of a paper trail to Shakespeare's life: when researching for my wife BA dissertation, we chased down a number of individuals, including the twice lord mayor of London and immensely rich merchant John Hende (admittedly two hundred years before Shakespeare). Hende appears mostly as a regular attender in court, usually on some money matter. He has no real outside existence and is a shadowy figure compared to his more famous contemporary, Richard Whittington. If we look at Shakespeare as Hende and de Vere as Whittington, we get an idea of how they really were. De Vere, after all, spent much time at the Court of Elizabeth I. Shakespeare was a jobbing actor and a playwright. The latter job isn't done in the limelight.

Back to what Feynman said. As I read Looney's first book, its sequel and those thick, lumpy volumes of his supporters, the sheer mass of evidence made the hypothesis seem convincing. But when I checked the facts, they dissolved one by one. Stratfordians, as they are rather insultingly labelled, back the traditional horse: Shakespeare was Shakespeare. And they hold all the aces. They don't have to argue about funny dates for the last few plays, or the first few, or whatever. They hold those aces because the original attribution is correct. We will learn more about Shakespeare as time goes by. Somewhere there must be more documents waiting to be uncovered, or scraps wrongly archived, that will give us just a tiny bit more of a biography of the Stratford, Warwickshire man. But the emotional pull of the Essex man was momentarily strong.

And wrong. I wanted de Vere to be the author that it tainted my thinking for a couple of months. It was just as it was when I read Erich von Daniken when I was at school (second year, now year 8, silent reading on a Friday morning - I was reading Return To The Stars) and thought there might be something in this. Well, I was wrong. I didn't know enough, and was impressionable, to realise that every if... was not a fact but a conjecture and that if it became a "fact" a few lines further on, it wasn't any more correct than it had been earlier. But as I learned more, I came to realise that pseudo-archaeology like this isn't good science at all. It is rubbish, corrosive pseudoscience. And it hides the deeper truths. We may have had alien visitations but this book and ones like it don't prove it. Not even close. But at 12 the idea was dynamite and I dearly wanted it to be true.

By checking these ideas against other books, or my own observations, I came to a deeper understanding. Quite often, the truth is dull, but it is only dull because it is the truth. Ideas can be true and exciting: evolution, relativity, quantum electrodynamics are all exciting and true and to many a mind can be dull. But how dull is it that all living things on the planet are connected at the deepest level of chemical reactions, or that gravity and mass are imperfect bedfellows, dancing around in space-time...

Einstein, of course, fooled himself into fiddling his equations to make a static universe because that's what he thought was the case. When it was discovered that the Universe was expanding, he was embarrassed. Who wouldn't be? But science is capable of accepting its mistakes and moving on from them. Still squabbling over the Shakespeare authorship question, Oxfordians have had the recent boost of a posh, expensive and downright wrong film, Anonymous, backed by such luminaries as (personal hero since I Claudius) Derek Jacobi. Science teaches that experts are only experts if the evidence backs them up. Sorry, Sir Derek, the evidence doesn't back the Oxford case. Edward de Vere, dilletante, bit time poet, forgotten playwright, part time warrior, courtier to Elizabeth I, isn't Shakespeare.

Saturday 31 December 2011

Friday 30 December 2011

Rob Buckman

I've just learnt, via the Daily Telegraph website that Doctor Rob Buckman has died. Perhaps saddest of all is that he died in October and the Telegraph has only just got around to publishing an obituary. A quick Google search shows that the Telegraph and I are behind the times. Everyone else seems to have put their obituaries out in October.

At the height of his fame, however, his body struck back when he developed dermatomyositis, an autoimmune disease that nearly killed him. After having rebuilt his life and career upon emigrating to Canada, he contracted a spinal chord disease that left him disable. In the end, he died in his sleep, although not without leaving a smile upon the face by doing so on a flight from London to Toronto.

He was working to the end, making a short series of films with Terry Jones of Python fame, on health the week before he died.

One medical reason for my undying gratitude to Rob Buckman is his book What You Really Need To Know About Cancer which I bought in early 1999 from a bookshop in Blackheath on the day that I found that my sister in law had secondary cancer in the liver. I wanted to know more about cancer and that book became, and remains, my go to reference. It is superb, unflinching and honest. It does not let the reader, be they a patient or a relative, down.

So thank you, Rob Buckman. And good bye.

Rob Buckman was a hero of mine when I was at school. He was so much that I wanted to be. He was successful, appearing on the TV rather frequently. He was knowledgeable. And he was funny. He looked a bit funny, as he would himself admit, but he had wit as well. He appeared on an ITV show called Don't Ask Me alongside fellow heroes Magnus Pyke, Miriam Stoppard and David Bellamy, running from 1974 to 1978. He contributed to the Radio 4 satire Weekending and had his own sketch show on ITVcalled The Pink Medicine Show.

He was working to the end, making a short series of films with Terry Jones of Python fame, on health the week before he died.

One medical reason for my undying gratitude to Rob Buckman is his book What You Really Need To Know About Cancer which I bought in early 1999 from a bookshop in Blackheath on the day that I found that my sister in law had secondary cancer in the liver. I wanted to know more about cancer and that book became, and remains, my go to reference. It is superb, unflinching and honest. It does not let the reader, be they a patient or a relative, down.

So thank you, Rob Buckman. And good bye.

Tuesday 27 December 2011

2012: The Year Ahead

January

Someone finally checks down the back of the CERN sofa and finds the Higgs Boson. In a statement released by his publicist, God denies any responsibility for the particle.

February

NASA put forward a new plan for a cheap alternative to the Space Shuttle for getting humans into orbit, the Moon, Mars and perhaps even beyond. The plan calls for a large balsa wood spaceship to be constructed, powered by an enormous rubber band. The project is costed at $75 but Congress strikes it down on the grounds than not enough dollars would be spent in marginal states in an election year.

March

Professor Brian Cox's new peaktime TV series, The Wonders Of The M25, is a massive success. The iconic shot of him standing, awestruck, in the car park at South Mimms service station, pointing in wonder at the RAC salesman by the main entrance, is reproduced on posters on student bedsit walls all over the world.

April

A team of palaeontologists working in south east Africa announces the finding of a tooth that is undoubtedly human in form but radiological dating puts it at 7 million years old. Immediately they announce a new missing link. Creationist websites decry the find and claim it to be no more than 6000 years old. In a statement released by his publicist, God says "Fight it out amongst yourselves."

May

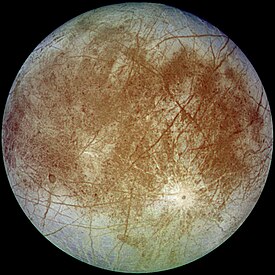

NASA announces it has discovered life on Jupiter's moon Europa. Barack Obama makes a statement from the Oval Office congratulating NASA for their discovery and US politicians, keen to be re-elected, find money to fund a manned mission to the satellite after working out that the high-tech nuts and bolts needed to build the craft can be made in their own marginal constituency.

June

Climate scientists are vindicated when Wimbledon has to be cancelled when temperatures reach 50C in Central London. The heatwave continues through the summer and follows the recent warming trends. Climate Change Denialists change their minds in droves.

July

Snow hits Central London and brings the traffic to a standstill. Climate Change Denialists say we told you so. God, in a statement released via his insurers, says ""Whoops, sorry, my bad."

August

Faster than light neutrinos are proven to be correct and with it the possibility of time travel. In a statement sent forwards in time by Albert Einstein, in the form of a letter that got lost in the post and only recently rediscovered, the great physicist says: "My bad".

September

David Attenborough's latest TV series, Life Not In The TV Studio, is criticised for being just a bit dull as not much is seen in spite of wildlife camera crews having been in the field for 15 years. One disgruntled viewer complained that all they saw in episode 1 was lions sleeping and antelopes eating grass.

October

Archaeologists at Stonehenge discover that the whole thing was built for the first Olympic Games held in Britain in 2500BC. A droll comment on the report says that the stadium is still waiting for a legacy use.

November

The British space programme gets a boost when a new, experimental rocket launch takes place. The rocket, 100 feet long (two hundred with the wooden stick), is launched from a specially built milk bottle on the 5th of the month. It completes a flawless suborbital mission when it bursts into a shower of red, white and blue sparkly lights over the North Sea.

December

Faster than light travel is found to have been going on for hundreds of years when a speed camera on the A403 captures a man in a red suit on a sleigh pulled by reindeer. The camera clocks him at 200,000 miles per second. When questioned by the police, he claims he is having to rush to deliver all the Wonders Of The M25 DVDs and Blu Rays to the children of the world in time for Christmas morning.

Someone finally checks down the back of the CERN sofa and finds the Higgs Boson. In a statement released by his publicist, God denies any responsibility for the particle.

February

NASA put forward a new plan for a cheap alternative to the Space Shuttle for getting humans into orbit, the Moon, Mars and perhaps even beyond. The plan calls for a large balsa wood spaceship to be constructed, powered by an enormous rubber band. The project is costed at $75 but Congress strikes it down on the grounds than not enough dollars would be spent in marginal states in an election year.

March

Professor Brian Cox's new peaktime TV series, The Wonders Of The M25, is a massive success. The iconic shot of him standing, awestruck, in the car park at South Mimms service station, pointing in wonder at the RAC salesman by the main entrance, is reproduced on posters on student bedsit walls all over the world.

April

A team of palaeontologists working in south east Africa announces the finding of a tooth that is undoubtedly human in form but radiological dating puts it at 7 million years old. Immediately they announce a new missing link. Creationist websites decry the find and claim it to be no more than 6000 years old. In a statement released by his publicist, God says "Fight it out amongst yourselves."

May

NASA announces it has discovered life on Jupiter's moon Europa. Barack Obama makes a statement from the Oval Office congratulating NASA for their discovery and US politicians, keen to be re-elected, find money to fund a manned mission to the satellite after working out that the high-tech nuts and bolts needed to build the craft can be made in their own marginal constituency.

June

Climate scientists are vindicated when Wimbledon has to be cancelled when temperatures reach 50C in Central London. The heatwave continues through the summer and follows the recent warming trends. Climate Change Denialists change their minds in droves.

July

Snow hits Central London and brings the traffic to a standstill. Climate Change Denialists say we told you so. God, in a statement released via his insurers, says ""Whoops, sorry, my bad."

August

Faster than light neutrinos are proven to be correct and with it the possibility of time travel. In a statement sent forwards in time by Albert Einstein, in the form of a letter that got lost in the post and only recently rediscovered, the great physicist says: "My bad".

September

David Attenborough's latest TV series, Life Not In The TV Studio, is criticised for being just a bit dull as not much is seen in spite of wildlife camera crews having been in the field for 15 years. One disgruntled viewer complained that all they saw in episode 1 was lions sleeping and antelopes eating grass.

October

Archaeologists at Stonehenge discover that the whole thing was built for the first Olympic Games held in Britain in 2500BC. A droll comment on the report says that the stadium is still waiting for a legacy use.

November

The British space programme gets a boost when a new, experimental rocket launch takes place. The rocket, 100 feet long (two hundred with the wooden stick), is launched from a specially built milk bottle on the 5th of the month. It completes a flawless suborbital mission when it bursts into a shower of red, white and blue sparkly lights over the North Sea.

December

Faster than light travel is found to have been going on for hundreds of years when a speed camera on the A403 captures a man in a red suit on a sleigh pulled by reindeer. The camera clocks him at 200,000 miles per second. When questioned by the police, he claims he is having to rush to deliver all the Wonders Of The M25 DVDs and Blu Rays to the children of the world in time for Christmas morning.

Monday 26 December 2011

Reasons to be cheerful; 1, 2, 3

Yesterday I had Christmas dinner with my dad. A pretty ordinary thing, you might think, were it not for the fact that at the start of the year that was something that looked very unlikely. Dad has three different kinds of cancer, and two of them played up in 2011.

The first to be diagnosed, in 1991, was a benign skin cancer that has resulted in my dad having a number of small tumours removed from his face over the last twenty years, and a number of skin grafts to repair the damage. As he says, he's not quite as handsome as he once was. Still, he is 81 so you can't expect his youthful good looks to be preserved.

In 1997 he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. The tumour was small, non-aggressive and easily treated, though the radiotherapy he had wasn't fun. But he took it all with good humour and got on with life.

But in 2006 he was found to have Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. It was in his abdomen, on the left hand side near but not in the pancreas. He had been unwell since October 2005 when he had a flu vaccination and felt a bit poorly. Eventually the doctors decided that something should be done so at the end of February 2006 dad found himself transported to hospital with the expectation that something would be done to cure him but most of all to find out what was wrong. Not that the latter was too difficult. Having visited my dad in hospital, my brother and I had a lengthy chat in the car park and both agreed it was cancer. When I saw the lump in my dad's side, that much was more than obvious.

Now we had the worst of the NHS. It took three weeks to work out what was wrong. Three weeks in which my dad got the sort of non-treatment that the newspapers occasionally highlight is given to the elderly in hospital. He was given plates of tepid food and expected to get on with it. He was observed but no one seemed in a rush to diagnose anything. He had a medic take five attempts to get a canula in his hand, eventually succeeding, having waited most of the day for anyone to come to tend to him. Finally, he got an MRI which told the doctors what we could have told them already it was cancer.

Now we got the best of the NHS. Treatment began within forty-eight hours. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in combination. I sat with him on one chemotherapy session, one of about ten he undertook. It was tedious. He sat in a chair, hooked up to the cocktail of cytotoxic chemicals that coursed through his veins, stopping the cancer cells in their tracks. And making his hair fall out. At least I could get up, go to the shop or the canteen, walk around. Dad had to sit, listen to the horse racing on the radio, read the paper, then read it again, have a snooze. And mum accompanied him without complaining.

Not that mum wasn't worried. She was but she wasn't prepared to think of the consequences if dad didn't pull through. And she had previous experience of cancer. Her mother had died of breast cancer in 1949, and my brother's first wife had also died of breast cancer in 2000. Before that, I remember my mum crying at the kitchen sink when told the news that my brother's best friend, Alan Frost, had died of testicular cancer at the age of 22. So she was right to be afraid.

As it was, dad got better and better. He had a buddy, our cat Bailey, who had been diagnosed with the same form of cancer in 2004. Whenever I chatted with my dad on the phone, he would ask about Bailey. Bailey was having the same steroids and regular chemotherapy tablets (which we had to give him, wearing plastic gloves so as not to get anything on our hands) and stayed healthy for 18 months before he had a steady decline and died in August 2006. Much missed.

Dad kept getting better and, with six monthly check ups all boding well, managed to get through the rather sudden loss of my mum, his wife of 58 years, in 2008. In September 2010 he had a comedy accident when he fell through my brother's ceiling (while my brother was away on honeymoon) after a leak occured in the roof. A few weeks later, he couldn't urinate and was taken in to hospital for treatment. Investigations suggested a tumour in the bladder which was later revised to pressure from a newly increased prostate. The prostate cancer was rearing its head and had spread to the bones, we were told.

At about the same time dad was having trouble with his vision and sought help from his GP who forwarded him to a specialist who forwarded him to the local cancer unit. How he made the deduction, I don't know, but a scan later and we knew that the reason for the sparkly thing in front of dad's vision was a number of tumours growing in his brain. He would be facing this without mum and there were some dark moments ahead. At Easter this year, he was bed ridden, his hair had dropped out, his weight had gone down alarmingy (and he was asking for smaller trousers). When we took him out it was in a wheelchair. He enjoyed the fresh air but I don't think he was enjoying life much.

And then he began to get better. I went down to see him and took my granddaughter with me. She clambered onto his bed and stole his grapes. At eighteen months, she was full of life and full of potential and I think my dad perked up in the face of such uninhibited life. What a wonderful therapy. The two love one another - if dad's not where the granddaughter thinks he should be, she gets grumpy. And if I don't take her, my dad asks why not.

So Christmas 2011 was the one my dad didn't think he would see so he assemble the family around him. His specialists, both of whom he saw in the week before Christmas, are happy with him. Both the malignant cancers are at a standstill. The treatments have done their job. His quality of life is good. The year is ending much better for my dad, and therefore the whole family, than it looked like doing. I hope to be saying similar things in a year's time.

The first to be diagnosed, in 1991, was a benign skin cancer that has resulted in my dad having a number of small tumours removed from his face over the last twenty years, and a number of skin grafts to repair the damage. As he says, he's not quite as handsome as he once was. Still, he is 81 so you can't expect his youthful good looks to be preserved.

In 1997 he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. The tumour was small, non-aggressive and easily treated, though the radiotherapy he had wasn't fun. But he took it all with good humour and got on with life.

But in 2006 he was found to have Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. It was in his abdomen, on the left hand side near but not in the pancreas. He had been unwell since October 2005 when he had a flu vaccination and felt a bit poorly. Eventually the doctors decided that something should be done so at the end of February 2006 dad found himself transported to hospital with the expectation that something would be done to cure him but most of all to find out what was wrong. Not that the latter was too difficult. Having visited my dad in hospital, my brother and I had a lengthy chat in the car park and both agreed it was cancer. When I saw the lump in my dad's side, that much was more than obvious.

Now we had the worst of the NHS. It took three weeks to work out what was wrong. Three weeks in which my dad got the sort of non-treatment that the newspapers occasionally highlight is given to the elderly in hospital. He was given plates of tepid food and expected to get on with it. He was observed but no one seemed in a rush to diagnose anything. He had a medic take five attempts to get a canula in his hand, eventually succeeding, having waited most of the day for anyone to come to tend to him. Finally, he got an MRI which told the doctors what we could have told them already it was cancer.

Now we got the best of the NHS. Treatment began within forty-eight hours. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in combination. I sat with him on one chemotherapy session, one of about ten he undertook. It was tedious. He sat in a chair, hooked up to the cocktail of cytotoxic chemicals that coursed through his veins, stopping the cancer cells in their tracks. And making his hair fall out. At least I could get up, go to the shop or the canteen, walk around. Dad had to sit, listen to the horse racing on the radio, read the paper, then read it again, have a snooze. And mum accompanied him without complaining.

Not that mum wasn't worried. She was but she wasn't prepared to think of the consequences if dad didn't pull through. And she had previous experience of cancer. Her mother had died of breast cancer in 1949, and my brother's first wife had also died of breast cancer in 2000. Before that, I remember my mum crying at the kitchen sink when told the news that my brother's best friend, Alan Frost, had died of testicular cancer at the age of 22. So she was right to be afraid.

As it was, dad got better and better. He had a buddy, our cat Bailey, who had been diagnosed with the same form of cancer in 2004. Whenever I chatted with my dad on the phone, he would ask about Bailey. Bailey was having the same steroids and regular chemotherapy tablets (which we had to give him, wearing plastic gloves so as not to get anything on our hands) and stayed healthy for 18 months before he had a steady decline and died in August 2006. Much missed.

Dad kept getting better and, with six monthly check ups all boding well, managed to get through the rather sudden loss of my mum, his wife of 58 years, in 2008. In September 2010 he had a comedy accident when he fell through my brother's ceiling (while my brother was away on honeymoon) after a leak occured in the roof. A few weeks later, he couldn't urinate and was taken in to hospital for treatment. Investigations suggested a tumour in the bladder which was later revised to pressure from a newly increased prostate. The prostate cancer was rearing its head and had spread to the bones, we were told.

At about the same time dad was having trouble with his vision and sought help from his GP who forwarded him to a specialist who forwarded him to the local cancer unit. How he made the deduction, I don't know, but a scan later and we knew that the reason for the sparkly thing in front of dad's vision was a number of tumours growing in his brain. He would be facing this without mum and there were some dark moments ahead. At Easter this year, he was bed ridden, his hair had dropped out, his weight had gone down alarmingy (and he was asking for smaller trousers). When we took him out it was in a wheelchair. He enjoyed the fresh air but I don't think he was enjoying life much.

And then he began to get better. I went down to see him and took my granddaughter with me. She clambered onto his bed and stole his grapes. At eighteen months, she was full of life and full of potential and I think my dad perked up in the face of such uninhibited life. What a wonderful therapy. The two love one another - if dad's not where the granddaughter thinks he should be, she gets grumpy. And if I don't take her, my dad asks why not.

So Christmas 2011 was the one my dad didn't think he would see so he assemble the family around him. His specialists, both of whom he saw in the week before Christmas, are happy with him. Both the malignant cancers are at a standstill. The treatments have done their job. His quality of life is good. The year is ending much better for my dad, and therefore the whole family, than it looked like doing. I hope to be saying similar things in a year's time.

Saturday 24 December 2011

Following a star

My first publication of a scientific observation came when I was twelve. It was in the august scientific journal, the Daily Mail and came about because I had written about seeing a meteor light up the sky to Big Chief I-Spy. He had a weekly column in the Daily Mail and, out of all the letters he must have got from precocious kids like me each day, he chose to highlight mine. My reward, other than ever-lasting fame, some kudos at school and two copies of that day's newspaper (rounded up by my dad), was a pen. No one ever said science paid well.

The thing I never mentioned in the letter was that the meteor explosion scared the hell out of me. When I was four, our house had been struck by lightning and this bolide (exploding meteoroid) resembled lightning (but without the thunder). It lit the sky up and the night it and I chose to be in the same rough location at the same time was Boxing Day 1974. Nearly forty years later I mostly remember the flash but I suppose it looked something like this:

At that time I had a star map on my bedroom wall where other young boys probably hung a poster of Suzi Quatro clipped from the pages of Look-In. I had a small telescope that was pretty good for showing features on the Moon's surface but was limited when trying to find the planets. I would wrap myself up and head out into the garden to look at the Moon almost nightly. In the summer I thought nothing of sitting in a folding chair in the garden trying to see meteors.

And meteors scared me. When I first found out about them it was through the pages of I-Spy The Sky. I can't remember how many points you got for seeing a meteor but it was fewer than a comet and more than for seeing something like Jupiter. What scared me was the fact that these lumps of rock could come out of the sky and land on the ground. I imagined that they would be hissing and steaming like the Martian ships in the original War Of The Worlds film (not starring Tom Cruise). When I first visited the Natural History Museum in the autumn of 1973 on a school trip, I made sure I went to see the meteorite gallery and I suppose I was somewhat disappointed. These frightening lumps of space rock were like misshapen cobbles. They seemed harmless.

In the main they are. No one is reported to have been killed by a fall and barely any falls have caused damage to humans or even their property. There are far too many square miles on the Earth's surface that are not occupied by humans, and then there's all that sea. But dozens of meteorites land on the surface each day and some of them are found. It's easier to look in the desert where vegetation doesn't obscure them, and better still to look on ice sheets because any rock on the surface of the ice almost certainly got there from the sky. But they do cause the odd bit of damage, as this Alabama woman found out first hand in

1954.

As result of other's endeavours, I have a small collection of meteorites. I am happy just to have my own selection of misshapen and scorched interplanetary pebbles but happier to have a piece of a meteorite chemically identical to rocks brought back by the Apollo astronauts. And I am happiest of all to have milligrammes of a stone that is reckoned to have played solar system pinball all the way from Mars. Instead of being frightened, I now cherish these rocks. They are my tiny connection with the vastness of space. Now that vastness does still frighten me, as it did Blaise Pascal three hundred or so years ago.

But I find the most amazing thing about this meteorite business is that we've found one on Mars.

This one was found in 2005 by the rover Opportunity. On Earth it would have turned to rust over the centuries but in the mainly carbon dioxide atmosphere of Mars it is perfectly preserved. So far the two rovers have found at least five, as discussed and illustrated here. One day, perhaps not too far off, an astronaut will kick their boot against a meteorite on the sandy martian surface and perhaps that rock will have begun its life here on Earth.

The thing I never mentioned in the letter was that the meteor explosion scared the hell out of me. When I was four, our house had been struck by lightning and this bolide (exploding meteoroid) resembled lightning (but without the thunder). It lit the sky up and the night it and I chose to be in the same rough location at the same time was Boxing Day 1974. Nearly forty years later I mostly remember the flash but I suppose it looked something like this:

At that time I had a star map on my bedroom wall where other young boys probably hung a poster of Suzi Quatro clipped from the pages of Look-In. I had a small telescope that was pretty good for showing features on the Moon's surface but was limited when trying to find the planets. I would wrap myself up and head out into the garden to look at the Moon almost nightly. In the summer I thought nothing of sitting in a folding chair in the garden trying to see meteors.

And meteors scared me. When I first found out about them it was through the pages of I-Spy The Sky. I can't remember how many points you got for seeing a meteor but it was fewer than a comet and more than for seeing something like Jupiter. What scared me was the fact that these lumps of rock could come out of the sky and land on the ground. I imagined that they would be hissing and steaming like the Martian ships in the original War Of The Worlds film (not starring Tom Cruise). When I first visited the Natural History Museum in the autumn of 1973 on a school trip, I made sure I went to see the meteorite gallery and I suppose I was somewhat disappointed. These frightening lumps of space rock were like misshapen cobbles. They seemed harmless.

In the main they are. No one is reported to have been killed by a fall and barely any falls have caused damage to humans or even their property. There are far too many square miles on the Earth's surface that are not occupied by humans, and then there's all that sea. But dozens of meteorites land on the surface each day and some of them are found. It's easier to look in the desert where vegetation doesn't obscure them, and better still to look on ice sheets because any rock on the surface of the ice almost certainly got there from the sky. But they do cause the odd bit of damage, as this Alabama woman found out first hand in

1954.

As result of other's endeavours, I have a small collection of meteorites. I am happy just to have my own selection of misshapen and scorched interplanetary pebbles but happier to have a piece of a meteorite chemically identical to rocks brought back by the Apollo astronauts. And I am happiest of all to have milligrammes of a stone that is reckoned to have played solar system pinball all the way from Mars. Instead of being frightened, I now cherish these rocks. They are my tiny connection with the vastness of space. Now that vastness does still frighten me, as it did Blaise Pascal three hundred or so years ago.

But I find the most amazing thing about this meteorite business is that we've found one on Mars.

This one was found in 2005 by the rover Opportunity. On Earth it would have turned to rust over the centuries but in the mainly carbon dioxide atmosphere of Mars it is perfectly preserved. So far the two rovers have found at least five, as discussed and illustrated here. One day, perhaps not too far off, an astronaut will kick their boot against a meteorite on the sandy martian surface and perhaps that rock will have begun its life here on Earth.

Friday 23 December 2011

Advertorial #2: How Apollo Flew To The Moon

The best book on Apollo I have ever read (correct me if there is a better one) is How Apollo Flew To The Moon by David Woods. Here is a link to a podcast with Woods talking about his book. Highly recommended. And here is the link to the author's website.

If you want to get one book on Apolo, this has to be the one.

If you want to get one book on Apolo, this has to be the one.

Hitch-Hiking

The Hitch Hiker's Guide To The Galaxy is going on tour. Members of the original cast are going to present a sort of reconstruction of the recording sessions. Could be interesting.

My interest in the Hitch Hiker's Guide To The Galaxy goes back to 1 March 1978. That's one week before the first episode was broadcast and my fifteenth birthday. It was when I heard the trailer for what was to be broadcast the following Wednesday on Radio 4 at 10.30pm. It was an intriguing trailer and I was determined to listen in a week's time. I was not disappointed.

I once read, though I probably made it up, that the truest Hitch Hiker's fans were the ones that thought the second radio series (1980) was the best thing of the entire multimedia presentation. Well, I happen to agree. The Total Perspective Vortex, the Man in the Shack, lemon soaked paper napkins (I cannot have even a second's delay on a flight without thinking about lemon soaked paper napkins), the Shoe Event Horizon, the inventiveness is endless.

I enjoyed the books, at least the first three, and the TV series was sort of all right, but the film never hit the spot for me, although some of it was quite funny. And Trillian in the film was better than Trillian on TV. But in the end there is nothing better than the invention that the listener brings through the power of his own mind. I listened in the dark, eyes closed to pick up every word, and when I got a stereo radio in 1979 I added earphones. But where I was, the reception on FM was atrocious so my first encounter with the second series was through a haze of hiss.

There have been stage performances before, ones directed by the late Ken Campbell (above, whom I met once, a lovely man, with a delight in the absurd, who told me a story about John Cleese - apparently Cleese would be a hunched figure off camera but when he was about to perform he would unwind like a fern and rise up to his full height). I'm looking forward to this new one.

Sadly, Ken Campbell is one of those from the original series no longer with us. Peter Jones (the book) died in 2000, Richard Vernon (Slartibartfast) died in 1997. Anthony Sharp (the Great Prophet Zarquon) died in 1984 and John Le Mesurier (the Wise Old Bird) in 1983. The radio producer most responsible forgetting the thing on the air, Geoffrey Perkins, died tragically in 2008 of natural causes. And, of course, the genius responsible for the entire thing, Douglas Adams, forgot where his towel was in 2001. Can it really be ten years since he died? I suppose it must be.

My interest in the Hitch Hiker's Guide To The Galaxy goes back to 1 March 1978. That's one week before the first episode was broadcast and my fifteenth birthday. It was when I heard the trailer for what was to be broadcast the following Wednesday on Radio 4 at 10.30pm. It was an intriguing trailer and I was determined to listen in a week's time. I was not disappointed.

I once read, though I probably made it up, that the truest Hitch Hiker's fans were the ones that thought the second radio series (1980) was the best thing of the entire multimedia presentation. Well, I happen to agree. The Total Perspective Vortex, the Man in the Shack, lemon soaked paper napkins (I cannot have even a second's delay on a flight without thinking about lemon soaked paper napkins), the Shoe Event Horizon, the inventiveness is endless.

I enjoyed the books, at least the first three, and the TV series was sort of all right, but the film never hit the spot for me, although some of it was quite funny. And Trillian in the film was better than Trillian on TV. But in the end there is nothing better than the invention that the listener brings through the power of his own mind. I listened in the dark, eyes closed to pick up every word, and when I got a stereo radio in 1979 I added earphones. But where I was, the reception on FM was atrocious so my first encounter with the second series was through a haze of hiss.

There have been stage performances before, ones directed by the late Ken Campbell (above, whom I met once, a lovely man, with a delight in the absurd, who told me a story about John Cleese - apparently Cleese would be a hunched figure off camera but when he was about to perform he would unwind like a fern and rise up to his full height). I'm looking forward to this new one.

Sadly, Ken Campbell is one of those from the original series no longer with us. Peter Jones (the book) died in 2000, Richard Vernon (Slartibartfast) died in 1997. Anthony Sharp (the Great Prophet Zarquon) died in 1984 and John Le Mesurier (the Wise Old Bird) in 1983. The radio producer most responsible forgetting the thing on the air, Geoffrey Perkins, died tragically in 2008 of natural causes. And, of course, the genius responsible for the entire thing, Douglas Adams, forgot where his towel was in 2001. Can it really be ten years since he died? I suppose it must be.

Douglas Adams 1952-2001

Geoffrey Perkins 1953-2008

Thursday 22 December 2011

Stonehenge in winter

Today is the Winter Solstice. Well it is here in the northern hemisphere. Anyway, at 5.30GMT this morning, the Sun reached it's southernmost point and has begun the northward journey back towards what passes for a summer in this pudding island of Great Britain. So a bunch of "druids" arrived at the enigmatic monument of Stonehenge to celebrate the fact. Obviously winter is not so hospitable as summer so many fewer turn up at this time of the year to see the sun rise at 8.03GMT (see here)..

But the whole alignment for Stonehenge is with the setting sun at the Winter Solstice. And if you are there when the sun goes down, you get this spectacular view. Like this

A simple examination of a plan of the site shows that the Summer Solstice is incidental and that the Winter one is the only one that matters.

But the whole alignment for Stonehenge is with the setting sun at the Winter Solstice. And if you are there when the sun goes down, you get this spectacular view. Like this

A simple examination of a plan of the site shows that the Summer Solstice is incidental and that the Winter one is the only one that matters.

The Stonehenge site is more than just the circle of stones and the attendant banks and ditches. It is a much wider landscape, including a processional way, known as the Avenue, which arcs all the way back to the river Avon.

Those celebrating the feast of the end of the year and the beginning of the new one would have walked the Avenue, turning about half a kilometre north east of the monument and catching sight of the setting Sun above the stones. Whether there was, as Mike Parker Pearson contends, a land of the living at Durrington Walls, and a land of the dead at Stonehenge doesn't matter here. It's a matter of logistics. A priest, followed by hundreds, perhaps thousands of followers, can't really turn around having walked the Avenue to see the rising sun. It only takes a bit of bad timing and there are people pushing to get in to see while others have already staked their places. This might not have been a big problem four thousand years ago but we know what happens when crowds get too excited or impatient. I cannot see how the Summer Solstice works as a festival here.

Winter festivals are important events. Ignoring the religious aspects, there was the practical one. Many animals were slaughtered at this time because food was scarce and the food to keep these animals alive was running out. So a feast of fresh meat at the time of the Winter Solstice was a practical thing. And the list of festivals at this time of the year is lengthy. Besides Christmas, there was the Saxon Yule, the Germanic Modraniht, , the Persian Yalda, the Roman Saturnalia and the Hindu Diwali. And that's just a selective list and it doesn't include those other winter festivals. I know there are midsummer festivals, most of which seem to include bonfires and some feasting, but the significance of the midwinter ones is obvious. The Sun is reborn at this time of the year. It dies then comes again.

Archaeologists are innovative people who have to come up with explanations or all sorts of mysterious finds with little to go on. The work done with Stonehenge (there was more only this week about the origin of the bluestones) has been fantastic. The problem is, we will never know the true reason for its construction, and later conversions and rebuildings. We can only speculate and argue our case.

Tuesday 20 December 2011

The Shroud Of Turin Meets Science (#94)

It's back. A group of scientists have done what scientists sometimes do and decided that it must be genuine because they've come up with a possible method (see here). Well, I don't want to comment on the science as such, but on something else that rarely gets a mention. Whoever is the subject of the shroud, they were a bit odd.

What I'd like to concentrate on are the arms. Look at this detail from the above photograph.

Notice anything? Try using a ruler to measure the distance from the point of the elbow to the end of the fingers for both arms. In most people the measurement would be the same for both arms, within a small margin of error. But for this poor subject, one arm is significantly longer than the other. This isn't my discovery. I learned it from Joe Nickell's book Inquest On The Shroud Of Turin that I read twenty years ago (updated edition available here). The answers usually given by those that believe the shroud to be genuine are... silence. But the physical proportions of the subject on the shroud are not typical (his total arm span is greater than his height, for instance). You don't need to be a scientist to sport that this isn't normal, and doesn't look at all like anything you've ever seen.

Science can answer the question of the shroud's authenticity. Carbon dating a few years back almost laid that one to rest and I am inclined to believe the date that it did produce - after all, it fit the documentary evidence and the stylistic evidence too (the subject has a lovely medieval face, not at all like those representations from before the "discovery" of the shroud in the thirteenth century). Science cannot answer the question of Jesus's divinity. That's a matter of faith. And here the shroud is no use at all. That's why some cling to the threads of any scientific report that suggests a supernatural explanation - or at least one beyond what we think the medieval artist was capable of. This is pretty much the argument from personal credulity that is beloved of creationists.

The latest report will probably soon be forgotten. A comment on it is here. There will be another one along in a couple of years, complete with the same philosophical premise.

What I'd like to concentrate on are the arms. Look at this detail from the above photograph.

Notice anything? Try using a ruler to measure the distance from the point of the elbow to the end of the fingers for both arms. In most people the measurement would be the same for both arms, within a small margin of error. But for this poor subject, one arm is significantly longer than the other. This isn't my discovery. I learned it from Joe Nickell's book Inquest On The Shroud Of Turin that I read twenty years ago (updated edition available here). The answers usually given by those that believe the shroud to be genuine are... silence. But the physical proportions of the subject on the shroud are not typical (his total arm span is greater than his height, for instance). You don't need to be a scientist to sport that this isn't normal, and doesn't look at all like anything you've ever seen.

Science can answer the question of the shroud's authenticity. Carbon dating a few years back almost laid that one to rest and I am inclined to believe the date that it did produce - after all, it fit the documentary evidence and the stylistic evidence too (the subject has a lovely medieval face, not at all like those representations from before the "discovery" of the shroud in the thirteenth century). Science cannot answer the question of Jesus's divinity. That's a matter of faith. And here the shroud is no use at all. That's why some cling to the threads of any scientific report that suggests a supernatural explanation - or at least one beyond what we think the medieval artist was capable of. This is pretty much the argument from personal credulity that is beloved of creationists.

The latest report will probably soon be forgotten. A comment on it is here. There will be another one along in a couple of years, complete with the same philosophical premise.

Monday 19 December 2011

Advertorial

Perhaps this isn't the done thing but never mind. I've put up a link in My Blog Roll to Spacecraft Films. This is a small (at least I assume it's small) American company that produces DVDs of superb quality containing unadulterated film and TV footage from American spaceflights. These are not necessarily for the casual viewer, perhaps more for the enthusiast (i.e. me) although a number of their products contain superb original documentaries (for example their Apollo 1 set, the Saturn V set and a few others). If you are into the Apollo progam in a big way then each and every set is worth having. I bought Apollo 15 first and never looked back.

Science at Christmas

Why did my brother get a chemistry set for Christmas one year? He wasn't really bothered by science. He was into motorbikes and soul music whereas I was the, ahem, nerd of the litter, the one who would demand to watch James Burke whenever he was on. So how come my brother got the chemistry set and I didn't?

Can't really answer that one, though I did get some sciency presents in my childhood years. The one I do remember well was a microscope, a small one, in a lovely wooden box. It might not have been overly powerful but it did provide nice views of protists from the local ponds when I had a pond dipping phase a few years later. Now I come to think of it, that microscope served me well.

The only other thing I can recall is the game Blast Off. Now, for reasons that I never quite got to terms with, the aim was to land on the Moon, or something like that. But the spaceships were Gemini, not Apollo, and they docked with Agena target vehicles, not lunar modules. All very confusing to someone who wanted accuracy. Not that I ever quite got to the bottom of the rules. I liked my games simple. For a review of the game, click here. I don't remember it being that simple.

Looking on Ebay, you'll find plenty on sale. It seems that everyone who had one must have hidden it in the loft and kept it in good condition. Not me. I gave mine away when I put away childish things and thought I might be grown up. But no man is ever so grown up that childish things are not attractive, and there is something Proustian about gazing upon the various pieces of the game and remembering the smell of the cardboard and sitting around a table with your friends trying to work out the rules. I bet you don't get that with your average Xbox game.

One thing I didn't get, although I asked Santa himself, in person, for it when I visited him at a department store in Chelmsford, was the Airfix Saturn V kit. This was the pinnacle, the Holy Grail, for a seven year old space fanatic like myself (and James May, apparently). He asked me what I wanted. I told him, but I didn't get it. Not for Christmas. I had to wait for my next birthday (all right, that was only two months but at that age there is disappointment and then there's this sort of disappointment). I made it, played with it, then put it on the shelf to display it. It was wonderful. It was equally wonderful when I made it again more than twenty years later, but when Airfix rereleased it the other year, I didn't bother. There might be a Proustian stimulus in the box, but there might also be disappointment. As Paul McCartney once said in a different context, you can't reheat a souffle.

Can't really answer that one, though I did get some sciency presents in my childhood years. The one I do remember well was a microscope, a small one, in a lovely wooden box. It might not have been overly powerful but it did provide nice views of protists from the local ponds when I had a pond dipping phase a few years later. Now I come to think of it, that microscope served me well.

The only other thing I can recall is the game Blast Off. Now, for reasons that I never quite got to terms with, the aim was to land on the Moon, or something like that. But the spaceships were Gemini, not Apollo, and they docked with Agena target vehicles, not lunar modules. All very confusing to someone who wanted accuracy. Not that I ever quite got to the bottom of the rules. I liked my games simple. For a review of the game, click here. I don't remember it being that simple.

Looking on Ebay, you'll find plenty on sale. It seems that everyone who had one must have hidden it in the loft and kept it in good condition. Not me. I gave mine away when I put away childish things and thought I might be grown up. But no man is ever so grown up that childish things are not attractive, and there is something Proustian about gazing upon the various pieces of the game and remembering the smell of the cardboard and sitting around a table with your friends trying to work out the rules. I bet you don't get that with your average Xbox game.

One thing I didn't get, although I asked Santa himself, in person, for it when I visited him at a department store in Chelmsford, was the Airfix Saturn V kit. This was the pinnacle, the Holy Grail, for a seven year old space fanatic like myself (and James May, apparently). He asked me what I wanted. I told him, but I didn't get it. Not for Christmas. I had to wait for my next birthday (all right, that was only two months but at that age there is disappointment and then there's this sort of disappointment). I made it, played with it, then put it on the shelf to display it. It was wonderful. It was equally wonderful when I made it again more than twenty years later, but when Airfix rereleased it the other year, I didn't bother. There might be a Proustian stimulus in the box, but there might also be disappointment. As Paul McCartney once said in a different context, you can't reheat a souffle.

Sunday 18 December 2011

A Night With The Stars

The other week the DailyTelegraph published an article pointing out how sexy science is at the moment ( http://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/8946805/Brian-Cox-and-co-sexy-science-pulls-in-the-crowds.html ). At last, I say. It's been a while since A Brief History Of Time when arts and humanities graduates were falling over themselves to say how they had reached page 23 of Steven Hawking's most famous work and understood, well, some of it. I read that book in a day (it isn't all that long) but because I had been prepared by earlier reading, I knew much of it already and it didn't seem all that difficult. But then I do have a BSc.

Tonight I watched the BBC's current favourite, Professor Brian Cox, give quite a challenging lecture on quantum theory to an audience comprised of a number of celebrities (and others I didn't recognise). The hour flashed by, and I learned plenty. I learned why the exclusion principle is true, for instance. I shall be rereading his first popular science book again as a result. It was good to see the BBC had the confidence to put a challenging science programme on at peak time on a main channel, BBC2. Science is truly sexy again.

Not only have we had Cox's Wonders programmes, but we've had two series on geology, two on human evolution, series on the history of science, on Darwin, on chemistry and maths in recenty years. And on Radio 4 is Prof Cox again, in the gloriously entertaining The Infinite Monkey Cage. And that's just the BBC. Channel 4 also puts out science programmes and it also seems content not to dumb down.

It got me thinking about the last time I could remember when science was so ubiquitous on the BBC. For me it was 1978-9. I was in my last year of compulsory education, approaching O-levels, and was helped by the presence of blockbuster series: David Attenborough's Life On Earth, James Burke's Connections, Jonathan Miller's The Body In Question and one off documentaries: Peter Ustinov explaining Einstein one Sunday afternoon, Dudley Moore getting to grips with time late one weekday night (when I should have been revising or in bed ready for an exam the next day). And there was Tomorrow's World and Horizon, the BBC's steady workhorses of science and technology.

I am sure some of the reviewers of Prof Cox's lecture will have misunderstood the thing. They will perhaps see the place of James May or Jonathan Ross as yet another sign that things are forever dumbing down. Perhaps they will have missed the calculation that Ross was "invited" to take part in, demonstrating how unlikely it is that an object, any object, that we can hold in our hands will leap suddenly through quantum processes a couple of inches to the left. As an explication of how science works, what science has achieved and how to teach it, the lecture was a triumph.

Tonight I watched the BBC's current favourite, Professor Brian Cox, give quite a challenging lecture on quantum theory to an audience comprised of a number of celebrities (and others I didn't recognise). The hour flashed by, and I learned plenty. I learned why the exclusion principle is true, for instance. I shall be rereading his first popular science book again as a result. It was good to see the BBC had the confidence to put a challenging science programme on at peak time on a main channel, BBC2. Science is truly sexy again.

Not only have we had Cox's Wonders programmes, but we've had two series on geology, two on human evolution, series on the history of science, on Darwin, on chemistry and maths in recenty years. And on Radio 4 is Prof Cox again, in the gloriously entertaining The Infinite Monkey Cage. And that's just the BBC. Channel 4 also puts out science programmes and it also seems content not to dumb down.

It got me thinking about the last time I could remember when science was so ubiquitous on the BBC. For me it was 1978-9. I was in my last year of compulsory education, approaching O-levels, and was helped by the presence of blockbuster series: David Attenborough's Life On Earth, James Burke's Connections, Jonathan Miller's The Body In Question and one off documentaries: Peter Ustinov explaining Einstein one Sunday afternoon, Dudley Moore getting to grips with time late one weekday night (when I should have been revising or in bed ready for an exam the next day). And there was Tomorrow's World and Horizon, the BBC's steady workhorses of science and technology.

I am sure some of the reviewers of Prof Cox's lecture will have misunderstood the thing. They will perhaps see the place of James May or Jonathan Ross as yet another sign that things are forever dumbing down. Perhaps they will have missed the calculation that Ross was "invited" to take part in, demonstrating how unlikely it is that an object, any object, that we can hold in our hands will leap suddenly through quantum processes a couple of inches to the left. As an explication of how science works, what science has achieved and how to teach it, the lecture was a triumph.

School days

I visited my old school last week. Or rather, I went to the site. My old school is now a few miles away from where it was when I went there and the site has been turned into a Sixth Form College but there is still enough of the old school present to bring back memories.

But it's not the memories but the name that is important here. My school was named after a scientist who inspired and influenced Galileo. It is named after Colchester resident and Royal physician William Gilberd (1544-1603).

Gilberd, or Gilbert, is known for his book De Magnete which studies the properties of magnets. To us that's child's play. Simple little experiments into attraction, repulson and force fields are done in schools around the world daily. The point is, Gilberd was the first to put together a book based largely on experimental results. It was that which inspired Galileo. Gilberd is one of the first scientists.

Although the book is about magnetism, Gilberd was actually searching for something much bigger. He wanted to establish the truth of Copernicus's model of the Solar System and was searching for something to make the model work. He didn't really achieve that but he did found something perhaps more important.

Magnetism has a much more useful sibling: electricity. Gilberd studied what he could of electricity, static electricity in those days, and gave us its name. Someone else would have come along and studied static but no doubt there would have been a different name. Gilberd stands on the cusp of the modern scientific world. He would be truly astonished, but also fascinated, by what electricity and magnetism has given us. But for modern electromagnetic wonders, we need to thank Michael Faraday.

But it's not the memories but the name that is important here. My school was named after a scientist who inspired and influenced Galileo. It is named after Colchester resident and Royal physician William Gilberd (1544-1603).

Gilberd, or Gilbert, is known for his book De Magnete which studies the properties of magnets. To us that's child's play. Simple little experiments into attraction, repulson and force fields are done in schools around the world daily. The point is, Gilberd was the first to put together a book based largely on experimental results. It was that which inspired Galileo. Gilberd is one of the first scientists.

Although the book is about magnetism, Gilberd was actually searching for something much bigger. He wanted to establish the truth of Copernicus's model of the Solar System and was searching for something to make the model work. He didn't really achieve that but he did found something perhaps more important.

Magnetism has a much more useful sibling: electricity. Gilberd studied what he could of electricity, static electricity in those days, and gave us its name. Someone else would have come along and studied static but no doubt there would have been a different name. Gilberd stands on the cusp of the modern scientific world. He would be truly astonished, but also fascinated, by what electricity and magnetism has given us. But for modern electromagnetic wonders, we need to thank Michael Faraday.

Saturday 17 December 2011

In the beginning there was...

I can date when I first became interested in science. In fact, I can do better than that. I can put a time on it. It was somewhere about 1.51pm, Saturday 21 December 1968.

That was when I sat bewitched by live television coverage of the launch of Apollo 8. As a five year old I didn't understand much, but I had a toy rocket launcher which resembled the Saturn V closely enough to my eyes to make a direct connection between me and the Kennedy Space Center. As I watched the countdown and launch, a lifelong passion was born.

I became a spaceflight nerd. I had to know everything and luckily I was also an avid reader, even at that young age. I stayed up late on the Sunday night that Apollo 11's lunar module touched down in the Sea of Tranquiliy, was picked out of my bed in the small hours to watch the moonwalk (although I was too sleepy to do more than raise the odd eyelid) and an agitator to have the school TV show it in class the following morning. We were a BBC family, so Apollo to me is indelibly associated with James Burke, Patrick Moore and Also Sprach Zarathustra.

One of the biggest disappointments of my young life was the failure of the camera on the surface during Apollo 12. I forgive Alan Bean - he's too nice a man to bear a grudge against - but it was my first chance properly to watch live pictures from the surface of the Moon and I was home too late from school to see what there was. And Apollo 13 didn't even reach the Moon. But Apollo 14 did and better still, Apollo 15 went to the Moon during the school holidays so there was no excuse for watching as much of it as I could. Fantastic.

The end of Apollo, then Skylab, coincided with a tailing off of my passion. I went on to secondary school, studied science seriously and found that biology was my best subject. So I pushed myself deeper and deeper into that. But I kept an eye on space, on Viking, on the development of the Shuttle, on what the Russians were up to. It still mattered a great deal to me, just it wasn't on the TV.

I suppose for someone who is old enough to have seen Apollo as it happened, the Shuttle wasn't such an exciting prospect. But I watched what I could on television, sat in Greenwich Park one Sunday afternoon to watch orbiter Enterprise fly past on the back of a 747, and dreamed one day of seeing a rocket launch. I had entered a competition in Look In magazine to go to the launch of Apollo 16 (I didn't win but then again I don't think I could have gone anyway since an adult would have had to accompany me and I don't think mum or dad were that keen). Well, I never did get to see a Shuttle launch though I was at KSC for a landing (all I heard were the sonic booms, I never saw the lander) and in 2009 I did see a Delta II rocket launch a satellite one twilight August morning. I filmed the launch. As the rocket lit up the dawn sky, you can clearly hear me go "Wow".

Well, here we are at a pause in spaceflight. NASA has plans, Congress has the pursestrings and the money is scarce. When you think of the generation of scientists and engineers made by watching Apollo, another voyage of discovery like that can only be good for the American and therefore the world economy. Apollo might have cost a vast amount of money, but none of it was spent anywhere other than on Earth. My granddaughter has just passed her second birthday. I'd dearly love her to be watching a launch to the Moon, Mars or an asteroid before she is too old to be anything but cynical about it. Fingers out, America. Make it happen.

That was when I sat bewitched by live television coverage of the launch of Apollo 8. As a five year old I didn't understand much, but I had a toy rocket launcher which resembled the Saturn V closely enough to my eyes to make a direct connection between me and the Kennedy Space Center. As I watched the countdown and launch, a lifelong passion was born.

I became a spaceflight nerd. I had to know everything and luckily I was also an avid reader, even at that young age. I stayed up late on the Sunday night that Apollo 11's lunar module touched down in the Sea of Tranquiliy, was picked out of my bed in the small hours to watch the moonwalk (although I was too sleepy to do more than raise the odd eyelid) and an agitator to have the school TV show it in class the following morning. We were a BBC family, so Apollo to me is indelibly associated with James Burke, Patrick Moore and Also Sprach Zarathustra.

One of the biggest disappointments of my young life was the failure of the camera on the surface during Apollo 12. I forgive Alan Bean - he's too nice a man to bear a grudge against - but it was my first chance properly to watch live pictures from the surface of the Moon and I was home too late from school to see what there was. And Apollo 13 didn't even reach the Moon. But Apollo 14 did and better still, Apollo 15 went to the Moon during the school holidays so there was no excuse for watching as much of it as I could. Fantastic.

The end of Apollo, then Skylab, coincided with a tailing off of my passion. I went on to secondary school, studied science seriously and found that biology was my best subject. So I pushed myself deeper and deeper into that. But I kept an eye on space, on Viking, on the development of the Shuttle, on what the Russians were up to. It still mattered a great deal to me, just it wasn't on the TV.

I suppose for someone who is old enough to have seen Apollo as it happened, the Shuttle wasn't such an exciting prospect. But I watched what I could on television, sat in Greenwich Park one Sunday afternoon to watch orbiter Enterprise fly past on the back of a 747, and dreamed one day of seeing a rocket launch. I had entered a competition in Look In magazine to go to the launch of Apollo 16 (I didn't win but then again I don't think I could have gone anyway since an adult would have had to accompany me and I don't think mum or dad were that keen). Well, I never did get to see a Shuttle launch though I was at KSC for a landing (all I heard were the sonic booms, I never saw the lander) and in 2009 I did see a Delta II rocket launch a satellite one twilight August morning. I filmed the launch. As the rocket lit up the dawn sky, you can clearly hear me go "Wow".

Well, here we are at a pause in spaceflight. NASA has plans, Congress has the pursestrings and the money is scarce. When you think of the generation of scientists and engineers made by watching Apollo, another voyage of discovery like that can only be good for the American and therefore the world economy. Apollo might have cost a vast amount of money, but none of it was spent anywhere other than on Earth. My granddaughter has just passed her second birthday. I'd dearly love her to be watching a launch to the Moon, Mars or an asteroid before she is too old to be anything but cynical about it. Fingers out, America. Make it happen.

Wednesday 14 December 2011

Welcome

I don't know if 2011 will be remembered as a milestone year in science but you've got to think so. Faster than light neutrinos (perhaps), a sign of where the Higgs Boson might be lurking (possibly) and obituaries for the demise of Intelligent Design all point in that direction. I'd love those three to be true. Then we can have tons of fun with the implications.

One of the reasons I am beginning this blog is to let teenagers know that science isn't boring. Having spent more than twenty years in and out of classrooms where a significant minority of teenagers are sitting and professing to be bored by science, I've seen it too often. And if there is one thing I can say, it's that science isn't boring. It's a fluid, dynamic subject. Perhaps it's the way it is taught, as a fossilised pile of knowledge. So when a big story comes along, one that actually makes the six o'clock news, then enough teenagers prick up their ears and science classrooms actually buzz with the sounds of interested young minds keen to learn more.

So let's hear it for the Large Hadron Collider, those speedy neutrinos and even the elusive Higgs Boson. They have set teenage tongues a-wagging. Thank you.

One of the reasons I am beginning this blog is to let teenagers know that science isn't boring. Having spent more than twenty years in and out of classrooms where a significant minority of teenagers are sitting and professing to be bored by science, I've seen it too often. And if there is one thing I can say, it's that science isn't boring. It's a fluid, dynamic subject. Perhaps it's the way it is taught, as a fossilised pile of knowledge. So when a big story comes along, one that actually makes the six o'clock news, then enough teenagers prick up their ears and science classrooms actually buzz with the sounds of interested young minds keen to learn more.

So let's hear it for the Large Hadron Collider, those speedy neutrinos and even the elusive Higgs Boson. They have set teenage tongues a-wagging. Thank you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)