I first came across New Scientist magazine in 1976. I was in W H Smith in Colchester High Street (shows how long ago it was - Smith's moved to the new Red Lion Shopping Precinct a few weeks later) and saw a picture of the surface of Mars on the cover. It was what I had been looking for - something that would tell me what the newly landed Viking probes had found. So I picked it up, checked the price, then joined the queue to pay for it. Took it home and made an effort to read it.

In those days, New Scientist was quite a dry, scientific journal. Articles were aimed at the moderately well educated and the professional scientist. Well, I wanted to be both and made a concerted effort to read it from cover to cover. It was not a great success because I didn't realise at the time just how much science I didn't know, but I was learning. Over the next couple of years, I bought another handful of issues before starting to read the magazine regularly in 1978. I haven't stopped since (the other magazine I have been reading for that long is Private Eye - I used to read Punch as well in those days but that folded twenty years ago).

This week's New Scientist has a small feature on vitamin D deficiency. It's something we teach occasionally in science lessons when we mention vitamins and minerals. Yes, we teach scurvy and its cure and mention rickets but... Perhaps we should mention it a bit more loudly. Vitamin D deficiency is on the rise.

Vitamin D is made in the skin using sunlight as an energy source and is readily available in many foods, including eggs, meat and fish. It is essential to get enough because the body needs it in an important way.

One of the compounds that vitamin D is converted to is calcitrol. Depending on where in the body the conversion takes place calcitrol can have two effects. In macrophage cells it acts to help prevent infection. If it is converted in the kidneys, it becomes a hormone. It is this latter use that is the most important as far as we are concerned because the hormone controls the levels of calcium and phosphate in the blood. It also has a neuromuscular effect, controlling cell proliferation and differentiation. In short, it is an important hormone.

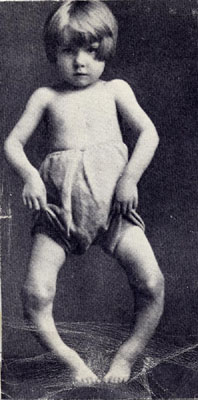

So what do you get if you don't get enough? The most famous is rickets, a commonplace of biology textbooks, in which the bones do not form correctly because the tissue is soft and weak. Long bones, especially those in the legs, become bowed.

Other diseases associated with vitamin D deficiency are osteoporosis, hyperparathyroidism, obesity and chronic backache. One disease perhaps less often associated with it in the minds of the public is depression. Vitamin D is believed to stimulate serotonin and that hormone is associated with mood. Furthermore, D is also linked to MS and asthma.

There were 762 cases of childhood rickets in the UK in 2010. This compares with 1550 or so cases of childhood cancer per year. Cancer clearly kills. Rickets is less obviously harmful but of course rickets is an extreme case and the incidence of vitamin D deficiency is probably far, far higher. The cause is perhaps trickier still to uncover, but lack of sunlight is surely one factor. Children are much more likely to be protected from sunshine than they were when I was young. 1976 was one long, hot summer. My grandmother told me the story of 1921, when she was thirty, and the drought went on seemingly forever. But in 1976, when I was not inside reading New Scientist, I was outside, playing football in the winter, cricket in the summer, and never once was my mum telling me to wear a hat or put on suncream.

Now, I don't advocate just letting your baby sit out in the sun all day, every day. Sunlight does cause skin cancer, but I am sure a little more sun and a little less suncream won't raise the incidence of skin cancers by more than an imperceptible jot.

No comments:

Post a Comment