When I was looking for a title for this blog, I looked up at my bookshelf and saw the vermillion spine of one book catching my eye. Ingenious Pursuits by Lisa Jardine. The book is an excellent history of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. I recommend it highly.

But I bring it up because the author, Lisa Jardine, has passed away from cancer at the age of 71. I owe her a big debt and will try to honour it by supporting science in the face of mindless criticisms that it faces from without and sometimes from within. From the distance that the printed pages lends, she taught me much. Her father was equally inspirational, Jacob Bronowski.

Monday, 26 October 2015

Sunday, 25 October 2015

Matt Ridley goes off piste again and gets a kicking

Once upon a time, there was a pretty good science writer named Matt Ridley. He worked for a prestigious magazine and wrote some entertaining and educating popular science books. Then he wrote a book more ideological than scientific, in parts scientifically wrong. Now he has published another book and it has been reviewed in the current issue of New Scientist. The book gets a kicking.

The kicking is not for the science but for the ideology, which the reviewer clearly does not agree with. Put simply, Ridley argues that there is too much regulation, including a whole wealth of regulation that his bank, Northern Rock, showed did not work. It is commonly held, amongst those that I talk to, that regulation was at fault in the 2008 crash and its wasn't because there was too much. Arguments might be made that national government should govern less, but I suspect those that argue that have little bits of protection they are not willing to give up. I bet Ridley is the same. His bank, and by extension himself, went cap in hand to the Bank of England to get them out of the hole they had dug themselves into by selling mortgages at both ends.

I haven't read the book but John Gray has and gives Ridley a similar kicking in the Guardian. Gray's review centres around Ridley's lack of historical mouse. Ideas that look like social Darwinism so often find events showing how wrong they are. Ridley seems to want to apply natural selection as an idea to the world of human ideas but it has a simple limitation that you might think someone as brainy as Ridley would have noticed: ideas do not live or die on which one is the best idea but which one has the most powerful proponents at the time. To an extent I am sympathetic to some of Ridley's earlier ideas. But I don't think small government works because powerful people seem to accrue more power where they can. It feels like a result of our evolution but it is nothing for which I have evidence and may easily be wrong. Confirmation bias makes it all too easy for me to go down that road but I stop myself following the logic to where it leads. Others don't, and it is those others that produce ideas that approach evil and sometimes reach it, both on the left and the right of the political spectrum.

I haven't read the book but Peter Forbes has in the Independent. He also says that Ridley has gone political in this book and the politics isn't pretty. Ridley, Forbes says, stresses the importance of evidence to science (although Ridley is a bit cavalier with evidence when it comes to climate science) yet he adduced anecdote and authorities to bolster his argument rather than evidence. Ridley, it seems, misses the effectiveness of central government in making much more peaceful societies than, say, the law enforcement of drug cartels in central and South America. If Ridley wants to write this book, I would hope he missed reading Steven Pinker's excellent The Better Angels Of Our Nature which is an immense evidence based triumph, showing how violence has declined over the course of history.

I haven't read the book and I doubt I will. One reason is an interview in the New York Times in which Ridley recommends Andrew Mountford's book The Hockey Stick Illusion as recommended reading for the Prime Minister. This is a book the reviewer in Prospect magazine called McCarthyite and not worth reading and Chemistry World described as pedantic. You would think Ridley would know better but he has been blinkered against the real story of climate change for twenty years or so. Even The Spectator is less keen on Ridley's thesis than one might have expected, following that magazines publication of some of his egregious articles on climate change. One line I enjoyed ridiculed Ridley's use of Nigel Lawson as a climate science authority. Ridley seems hamstrung by his desire to present a nature red in tooth and claw selection process for ideas that he misses some of the successes of ideas helped along but the very things he wrote about in The Origin Of Virtue all those years ago. Humans are both hierarchical and social, following leaders and helping one another. The best governments use those basics wisely. Science is powerful because it subverts individualism into a collective but competitive endeavour. Watson and Crick get all that credit for discovering the structure of DNA and sir paper in Nature is recalled to this day. The next paper along in the same edition was by Wilkins and Franklin and supplied details of the evidence Watson and Crick used. Here is an example of the competitive and cooperative nature of a human endeavour. Simplistic, perhaps, but real in many respects (I await comments that give me better understanding here).

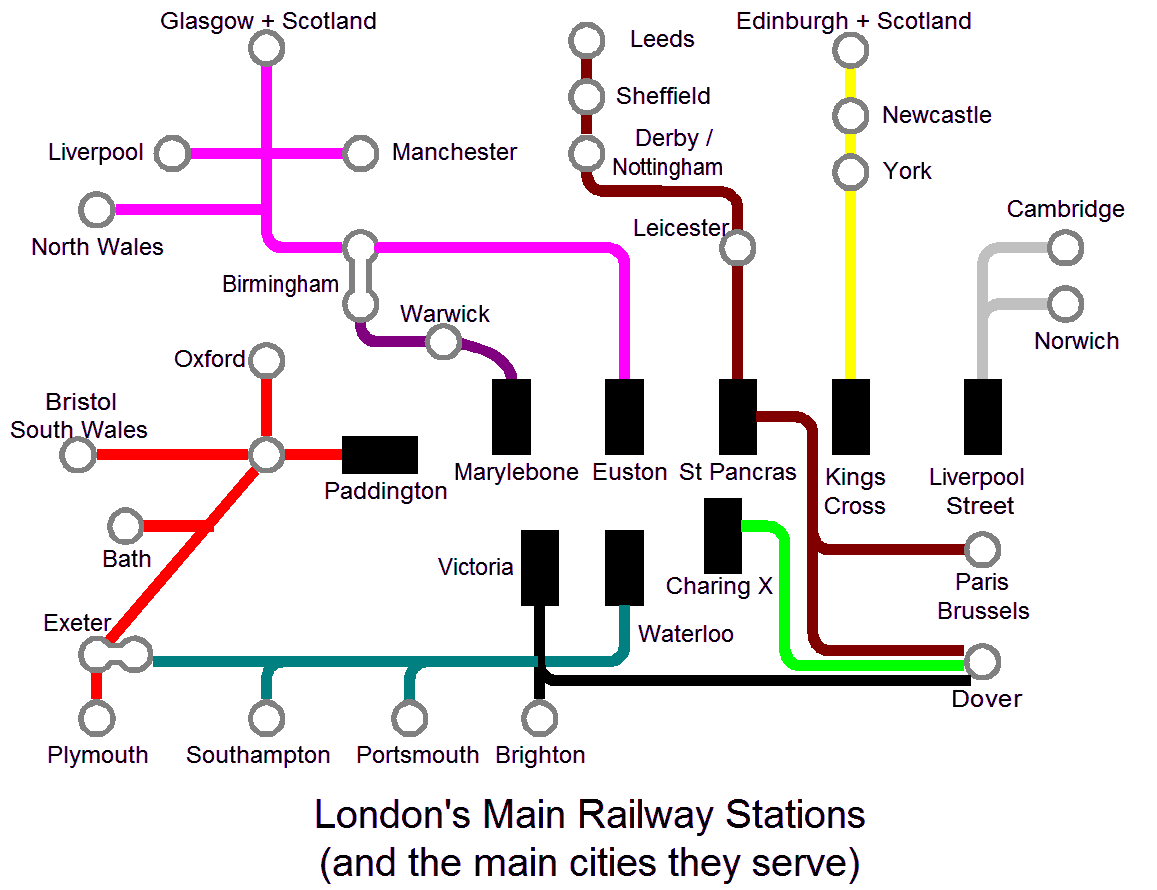

Ridley's thesis is that bottom up solutions work better than top down ones through a more organic process, a more evolutionary process. Counter examples are not hard to find. Take, for instance, the railway system of London. That's the mainline, overground system. This schematic shows how wonderfully logical the termini appear.

But this is a modern version. Following lengthy reorganisation, and omits some terminus stations and does not show the actual locations of them. This, more realistic map, shows a deeper truth.

There were extra termini at Bricklayers Arms, Cannon Street (still exists), Farringdon Street, Broad Street (no longer in existence but was right next to Liverpool Street), not to mention Fenchurch Station (the one on the British Monopoly board that no one has heard of otherwise). There are others I haven't mentioned. The system grew because individual companies built the lines and there was no overarching plan. London's railway system battles that lack of planning to this day. Lines approaching Charing Cross reach a bottleneck just where it would be advantageous for them to open out into more lanes. Hemmed in by buildings and streets, there is no room for expansion.

We should not forget that to build a railway in nineteenth century Britain, an Act of Parliament had to be sought.

Ridley's current book is his second that goes off his scientific piste and into more political snow. The consensus of the reviews I read suggests the science is well received but the politics less so. This is not surprising, because in the UK there is nothing similar to the US Tea Party movement and although UKIP polled well in the May General Election, there seems to be a feeling that, actually, their one shot at a breakthrough failed. There is a temptation to chat to your own and have your opinions confirmed but Ridley ought to know better. He has a scientific background and many of the scientists he looks up to are mainstream scientists who express the need for both a sceptical view and a careful, fact checking outlook. But Ridley has bought heavily into a substantially right of centre worldview with regards regulation and government. The success of Japan, for instance, demonstrates that small government can be trumped by big government.

Why did Ridley get his biology so right, in my opinion, yet his climate science so wrong? I cannot put my finger on it but one possibility is that he is of a generation that thinks technology is the answer to everything. Look at how his (and my) technological world has changed: we listened to large valve radios, watched black and white TV and had fixed, landline phones. Now we carry in our pockets a miniature device that will allow us to do each of those three things, and more, wherever and whenever we wish. In 1979, my school had a computer room which did what it said. It housed the computer. Within a couple of years, the BBC's computer push led to computer rooms in schools which housed class sets of computers. They might have been ancient boxes of electronics from the stone age compared to what we can do now, but they revolutionised school IT in the UK.

So being optimistic that humans can change the world is something Ridley and I can point a finger at and say it happened, and for the better (in general). But there is no evidence that such optimism will always work out. In fact, the technological solutions to worldwide problems (ozone hole, infectious diseases, etc) also requires international cooperation and big government. Locally based conservation groups can do much, and they do, but to make the necessary impact to solve global issues, global teamwork is essential.

But the most disappointing thing about Ridley is recent years has been his decline into the same old denialist tropes that he really should have been clever enough to avoid. In his own self-justification, What the climate wars did for science there is much on show that betrays Ridley's slack work. He inflates non-experts to the level of experts. For example, our old friend Jim Steele becomes a distinguished ecologist when in fact distinguished and ecologist are hardly appropriate for someone with only a self published book on his publication list. Steele has what appears to be a vendetta against Camille Parmesan but, unsurprisingly, Ridley takes Steele's side (even when an explanation for Parmesan's actions has been published) and cites wattsUpWithThat as support.

Unsurprisingly also, Ridley cites Lysenkoism in his whine about climate science. It looks as if Ridley has gone through the list of debunked and failed arguments at Skeptical Science and decided they look tasty when in fact they are ready to become pig swill. Read what Ridley wrote in self justification and try not to spray your screen with coffee. It is sometimes hard to remove from the keyboard. For someone who has spent a lifetime working around scientists, reading scientific papers and translating them for a less scientifically literature readership, Ridley's justification is riddled (pun intended) with arguments that don't work and never will. His audience will applaud his assertion that Tol has demolished Cook13's consensus measurement. That Tol has failed to do so, has been shown to be a ridiculous figure in this (by asserting 300 papers that don't exist) and for pursuing it when he really should have given up, isn't mentioned and won't be. Inconvenient that Jonathan Powell in the latest issue of the Skeptical Inquirer argues that Cook13 is, indeed, wrong. Powell says the consensus is really 99% and more. Pity the article is paywalled as it should be read by all deniers and should annoy them intensely. The logic Powell uses is impeccable, so far as I can see.

Ridley ends his justification on a downbeat note. Having cherry picked and misrepresented a pile of denier/realist confrontations, he says:

The kicking is not for the science but for the ideology, which the reviewer clearly does not agree with. Put simply, Ridley argues that there is too much regulation, including a whole wealth of regulation that his bank, Northern Rock, showed did not work. It is commonly held, amongst those that I talk to, that regulation was at fault in the 2008 crash and its wasn't because there was too much. Arguments might be made that national government should govern less, but I suspect those that argue that have little bits of protection they are not willing to give up. I bet Ridley is the same. His bank, and by extension himself, went cap in hand to the Bank of England to get them out of the hole they had dug themselves into by selling mortgages at both ends.

I haven't read the book but John Gray has and gives Ridley a similar kicking in the Guardian. Gray's review centres around Ridley's lack of historical mouse. Ideas that look like social Darwinism so often find events showing how wrong they are. Ridley seems to want to apply natural selection as an idea to the world of human ideas but it has a simple limitation that you might think someone as brainy as Ridley would have noticed: ideas do not live or die on which one is the best idea but which one has the most powerful proponents at the time. To an extent I am sympathetic to some of Ridley's earlier ideas. But I don't think small government works because powerful people seem to accrue more power where they can. It feels like a result of our evolution but it is nothing for which I have evidence and may easily be wrong. Confirmation bias makes it all too easy for me to go down that road but I stop myself following the logic to where it leads. Others don't, and it is those others that produce ideas that approach evil and sometimes reach it, both on the left and the right of the political spectrum.

I haven't read the book but Peter Forbes has in the Independent. He also says that Ridley has gone political in this book and the politics isn't pretty. Ridley, Forbes says, stresses the importance of evidence to science (although Ridley is a bit cavalier with evidence when it comes to climate science) yet he adduced anecdote and authorities to bolster his argument rather than evidence. Ridley, it seems, misses the effectiveness of central government in making much more peaceful societies than, say, the law enforcement of drug cartels in central and South America. If Ridley wants to write this book, I would hope he missed reading Steven Pinker's excellent The Better Angels Of Our Nature which is an immense evidence based triumph, showing how violence has declined over the course of history.

I haven't read the book and I doubt I will. One reason is an interview in the New York Times in which Ridley recommends Andrew Mountford's book The Hockey Stick Illusion as recommended reading for the Prime Minister. This is a book the reviewer in Prospect magazine called McCarthyite and not worth reading and Chemistry World described as pedantic. You would think Ridley would know better but he has been blinkered against the real story of climate change for twenty years or so. Even The Spectator is less keen on Ridley's thesis than one might have expected, following that magazines publication of some of his egregious articles on climate change. One line I enjoyed ridiculed Ridley's use of Nigel Lawson as a climate science authority. Ridley seems hamstrung by his desire to present a nature red in tooth and claw selection process for ideas that he misses some of the successes of ideas helped along but the very things he wrote about in The Origin Of Virtue all those years ago. Humans are both hierarchical and social, following leaders and helping one another. The best governments use those basics wisely. Science is powerful because it subverts individualism into a collective but competitive endeavour. Watson and Crick get all that credit for discovering the structure of DNA and sir paper in Nature is recalled to this day. The next paper along in the same edition was by Wilkins and Franklin and supplied details of the evidence Watson and Crick used. Here is an example of the competitive and cooperative nature of a human endeavour. Simplistic, perhaps, but real in many respects (I await comments that give me better understanding here).

Ridley's thesis is that bottom up solutions work better than top down ones through a more organic process, a more evolutionary process. Counter examples are not hard to find. Take, for instance, the railway system of London. That's the mainline, overground system. This schematic shows how wonderfully logical the termini appear.

But this is a modern version. Following lengthy reorganisation, and omits some terminus stations and does not show the actual locations of them. This, more realistic map, shows a deeper truth.

There were extra termini at Bricklayers Arms, Cannon Street (still exists), Farringdon Street, Broad Street (no longer in existence but was right next to Liverpool Street), not to mention Fenchurch Station (the one on the British Monopoly board that no one has heard of otherwise). There are others I haven't mentioned. The system grew because individual companies built the lines and there was no overarching plan. London's railway system battles that lack of planning to this day. Lines approaching Charing Cross reach a bottleneck just where it would be advantageous for them to open out into more lanes. Hemmed in by buildings and streets, there is no room for expansion.

We should not forget that to build a railway in nineteenth century Britain, an Act of Parliament had to be sought.

Ridley's current book is his second that goes off his scientific piste and into more political snow. The consensus of the reviews I read suggests the science is well received but the politics less so. This is not surprising, because in the UK there is nothing similar to the US Tea Party movement and although UKIP polled well in the May General Election, there seems to be a feeling that, actually, their one shot at a breakthrough failed. There is a temptation to chat to your own and have your opinions confirmed but Ridley ought to know better. He has a scientific background and many of the scientists he looks up to are mainstream scientists who express the need for both a sceptical view and a careful, fact checking outlook. But Ridley has bought heavily into a substantially right of centre worldview with regards regulation and government. The success of Japan, for instance, demonstrates that small government can be trumped by big government.

Why did Ridley get his biology so right, in my opinion, yet his climate science so wrong? I cannot put my finger on it but one possibility is that he is of a generation that thinks technology is the answer to everything. Look at how his (and my) technological world has changed: we listened to large valve radios, watched black and white TV and had fixed, landline phones. Now we carry in our pockets a miniature device that will allow us to do each of those three things, and more, wherever and whenever we wish. In 1979, my school had a computer room which did what it said. It housed the computer. Within a couple of years, the BBC's computer push led to computer rooms in schools which housed class sets of computers. They might have been ancient boxes of electronics from the stone age compared to what we can do now, but they revolutionised school IT in the UK.

So being optimistic that humans can change the world is something Ridley and I can point a finger at and say it happened, and for the better (in general). But there is no evidence that such optimism will always work out. In fact, the technological solutions to worldwide problems (ozone hole, infectious diseases, etc) also requires international cooperation and big government. Locally based conservation groups can do much, and they do, but to make the necessary impact to solve global issues, global teamwork is essential.

But the most disappointing thing about Ridley is recent years has been his decline into the same old denialist tropes that he really should have been clever enough to avoid. In his own self-justification, What the climate wars did for science there is much on show that betrays Ridley's slack work. He inflates non-experts to the level of experts. For example, our old friend Jim Steele becomes a distinguished ecologist when in fact distinguished and ecologist are hardly appropriate for someone with only a self published book on his publication list. Steele has what appears to be a vendetta against Camille Parmesan but, unsurprisingly, Ridley takes Steele's side (even when an explanation for Parmesan's actions has been published) and cites wattsUpWithThat as support.

Unsurprisingly also, Ridley cites Lysenkoism in his whine about climate science. It looks as if Ridley has gone through the list of debunked and failed arguments at Skeptical Science and decided they look tasty when in fact they are ready to become pig swill. Read what Ridley wrote in self justification and try not to spray your screen with coffee. It is sometimes hard to remove from the keyboard. For someone who has spent a lifetime working around scientists, reading scientific papers and translating them for a less scientifically literature readership, Ridley's justification is riddled (pun intended) with arguments that don't work and never will. His audience will applaud his assertion that Tol has demolished Cook13's consensus measurement. That Tol has failed to do so, has been shown to be a ridiculous figure in this (by asserting 300 papers that don't exist) and for pursuing it when he really should have given up, isn't mentioned and won't be. Inconvenient that Jonathan Powell in the latest issue of the Skeptical Inquirer argues that Cook13 is, indeed, wrong. Powell says the consensus is really 99% and more. Pity the article is paywalled as it should be read by all deniers and should annoy them intensely. The logic Powell uses is impeccable, so far as I can see.

Ridley ends his justification on a downbeat note. Having cherry picked and misrepresented a pile of denier/realist confrontations, he says:

I dread to think what harm this episode will have done to the reputation of science in general when the dust has settled.He is right for all the wrong reasons. The reputation of science is being dirtied deliberately. Now we know that Exxon sat on research about climate change while giving support for denial, one wonders how Ridley will take that on board. How did he respond to Merchants Of Doubt, both book and movie? Ridley's one sided take on the climate debate is weird for someone who so clearly gets the science of evolution, when that side is to misrepresent evidence and mishear the debate. That there is a debate on the science itself is odd. That Ridley should be so clearly wrong suggests one thing and one thing only. His recent books give the answer: he listens to his politics on this one and not what the science says. When someone says the hockey stick graph is a scandal, you know they're wrong.

Sunday, 18 October 2015

Did the BBC base Count Arthur Strong on Lord Christopher Monckton?

Significant similarities between the fictional character, Lord Christopher Monckton, and the former variety star and current subject of a BBC reality TV series, the eponymous Count Arthur Strong, have been revealed in an investigation into the well known left wing bias of the BBC. It is so well known that we don't need to detail any of it here.

The similarities are too close to be described as anything but uncanny, though that has never stopped Lord Monckton from making a logical leap too many and allege a deliberate act. So let's examine the evidence and, as ever, let the reader make up their own mind (though, of course, the evidence will be presented in such a way that no one will be able to do anything than accept my conclusions).

1. The look

Monckton has been dressed in his fictional world in the tweeds and paraphenalia of the minor and not long established aristocracy.

Strong dresses in tweedy clothes befitting his aspirations to be seen as a real aristocrat but who really can only trace his dynasty in the peerage back to 1947 when his grandfather was ennobled for services to appeasement.

2 Mode of speech

Monckton's writers have given him a speaking style that means he says things that sound quite impressively intelligent but are actually gibberish. Watch this sketch from his ITV4 sketch show, The Christopher Monckton Half Hour.

Count Arthur Strong has a natural gift for talking nonsense, tripping over his words and making malapropisms, in spite of his eminence as a variety performer and actor (he narrowly lost out to Sean Connery for the role of James Bond in the early sixties). But amongst it all he has the natural charm of someone who is descended from a long line of two preceding Count Strongs.

3 The Politics

I think it is impossible to discount this piece of evidence. The two are identical, politcally. Here is that evidence. Read this spoof article from the website, BatShitCrazy.com, a satirical website hosted in America where the craziest and most stupid ideas are presented as if they were true. Here, the writers behind Lord Christopher Monckton, have come up with a hilarious article that would be good enough for Punch, were Punch still a going concern. To give you a flavour, let me quote a paragraph. I am sure you will get the point:

uncanny so close to identical as to be evidence of a conspiracy by the BBC

4 Current career

Lord Monckton's writers have given him a career of going to small halls and giving illustrated talks to bored housewives and those sheltering from the unseasonably extreme rainfall and/or heatwave. The writers expect us to see his failure to live up to his ambition to be a scientific expert, legal expert and stand up comedian with the sympathy you normally reserve for those that have tried but failed and as still in reception class at infants school.

Strong earns his living these days, since no one will seriously employ him as an entertainer, giving talks about his heyday on stage and TV pilot shows. You might notice that no one laughs at the jokes which fail miserably and we are asked, in the BBC reality show that follows him around with a camera crew, to be sympathetic to this rather lonely and sad character.

It is clear, then, that the BBC has based its reality series on the celebrated variety star and film and TV celebrity Count Arthur Strong on the fictional life of the bat shit crazy Lord Christopher Monckton. Case closed. Except to point out that "Lord Christopher Monckton" needs to be put into quotation marks. It's what he would have wanted, if he existed.

The similarities are too close to be described as anything but uncanny, though that has never stopped Lord Monckton from making a logical leap too many and allege a deliberate act. So let's examine the evidence and, as ever, let the reader make up their own mind (though, of course, the evidence will be presented in such a way that no one will be able to do anything than accept my conclusions).

1. The look

Monckton has been dressed in his fictional world in the tweeds and paraphenalia of the minor and not long established aristocracy.

Strong dresses in tweedy clothes befitting his aspirations to be seen as a real aristocrat but who really can only trace his dynasty in the peerage back to 1947 when his grandfather was ennobled for services to appeasement.

2 Mode of speech

Monckton's writers have given him a speaking style that means he says things that sound quite impressively intelligent but are actually gibberish. Watch this sketch from his ITV4 sketch show, The Christopher Monckton Half Hour.

Count Arthur Strong has a natural gift for talking nonsense, tripping over his words and making malapropisms, in spite of his eminence as a variety performer and actor (he narrowly lost out to Sean Connery for the role of James Bond in the early sixties). But amongst it all he has the natural charm of someone who is descended from a long line of two preceding Count Strongs.

3 The Politics

I think it is impossible to discount this piece of evidence. The two are identical, politcally. Here is that evidence. Read this spoof article from the website, BatShitCrazy.com, a satirical website hosted in America where the craziest and most stupid ideas are presented as if they were true. Here, the writers behind Lord Christopher Monckton, have come up with a hilarious article that would be good enough for Punch, were Punch still a going concern. To give you a flavour, let me quote a paragraph. I am sure you will get the point:

Now watch this clip of Count Arthur Strong making a political speech and you will have to admit that the similarities areThe madness of the governing class has now infected even the normally quite sensible British courts. For 1,000 years, the High Court in London has been dispensing (or, depending on your point of view, dispensing with) justice. A few years back, it decided to rebrand itself the “Supreme Court.” Next year, no doubt, it will be calling itself the “Pangalactic Court.”This normally staid and sensible body of custard-faced judges has now joined in the collective madness that is the global-warming scam. Lord Carnwath, a rabid environmentalist who has much the same opinion on climate change as Prince Charles (in a word, flaky), recently held an international conference of lawyers and judges on the theme of ganging up together to prosecute, convict and imprison scientists and researchers who, like me, commit the crime of conducting diligent scientific research and publishing the results in the learned journals from time to time.In the future, if Lord Carbuncle gets his way, an inexpert panel of international judges will review our research and pronounce on the extent to which it conforms to the climate-communist party line he so passionately espouses. Those of us whose research dares to point out, for instance, that the data show no global warming for approaching 19 years even though one-third of man’s supposed warming influence since 1750 has occurred over the same period will be found to have committed truth-crime and we will be locked up.

4 Current career

Lord Monckton's writers have given him a career of going to small halls and giving illustrated talks to bored housewives and those sheltering from the unseasonably extreme rainfall and/or heatwave. The writers expect us to see his failure to live up to his ambition to be a scientific expert, legal expert and stand up comedian with the sympathy you normally reserve for those that have tried but failed and as still in reception class at infants school.

Strong earns his living these days, since no one will seriously employ him as an entertainer, giving talks about his heyday on stage and TV pilot shows. You might notice that no one laughs at the jokes which fail miserably and we are asked, in the BBC reality show that follows him around with a camera crew, to be sympathetic to this rather lonely and sad character.

It is clear, then, that the BBC has based its reality series on the celebrated variety star and film and TV celebrity Count Arthur Strong on the fictional life of the bat shit crazy Lord Christopher Monckton. Case closed. Except to point out that "Lord Christopher Monckton" needs to be put into quotation marks. It's what he would have wanted, if he existed.

Sunday, 11 October 2015

Consensus by jury

Science, we are constantly reminded, does not proceed by consensus. And indeed it doesn't.

Science proceeds according to the evidence. However, as more evidence accrues, it becomes clearer and clearer that the idea being tested is correct, or at least the best explanation available at the moment. A consensus accretes around that idea and science and scientists accept that it is correct.

In the fields that I studied a little while ago, the description of the action potential in a neuron is consensus because it is extremely unlikely that the basics of the physical chemistry involved will be found to be wrong. Perhaps in one or two animals but the basics will be correct. And those neurophysiologists who study the action of neurons, there is barely likely to be a mention of whether or not they accept the current theory of action potentials. They just get on with improving our understanding until its polish gleams.

Our denier friends don't like the idea of consensus. They don't like the idea that scientists either agree with the evidence or they don't. They don't like the thought that more and more scientists cluster around and agree an understanding. It would be weird if scientists didn't work like that. It would be weird if they all decided to accept different ideas and no one agreed with anyone else.

It is how our legal system works. When tried by a jury of my peers, I expect them to assess the evidence and come to an understanding of who was responsible for the particular crime. I expect them to come to an agreement. After all, the evidence can only point one direction, depending upon how good the evidence is.

A unanimous verdict of the jury is a 100% consensus. 11 to 1 is 91.67%. 10 to 2 is 83.33%.

83.33% consensus is good enough in some trials to secure a conviction.

I think 97% is good enough consensus to allow us to say that global warming is caused by humans.

Science proceeds according to the evidence. However, as more evidence accrues, it becomes clearer and clearer that the idea being tested is correct, or at least the best explanation available at the moment. A consensus accretes around that idea and science and scientists accept that it is correct.

In the fields that I studied a little while ago, the description of the action potential in a neuron is consensus because it is extremely unlikely that the basics of the physical chemistry involved will be found to be wrong. Perhaps in one or two animals but the basics will be correct. And those neurophysiologists who study the action of neurons, there is barely likely to be a mention of whether or not they accept the current theory of action potentials. They just get on with improving our understanding until its polish gleams.

Our denier friends don't like the idea of consensus. They don't like the idea that scientists either agree with the evidence or they don't. They don't like the thought that more and more scientists cluster around and agree an understanding. It would be weird if scientists didn't work like that. It would be weird if they all decided to accept different ideas and no one agreed with anyone else.

It is how our legal system works. When tried by a jury of my peers, I expect them to assess the evidence and come to an understanding of who was responsible for the particular crime. I expect them to come to an agreement. After all, the evidence can only point one direction, depending upon how good the evidence is.

A unanimous verdict of the jury is a 100% consensus. 11 to 1 is 91.67%. 10 to 2 is 83.33%.

83.33% consensus is good enough in some trials to secure a conviction.

I think 97% is good enough consensus to allow us to say that global warming is caused by humans.

Lynne McTaggart's Holy Implausible

She's at it again. In a blog post entitled Holy Water, McTaggart thinks she understands what she clearly doesn't understand - science.

McTaggart has decided to take on water because it is the last refuge of the homeopath clinging to their discredited idea. If, and it is a pleading, longing, highly optimistic if, water can be found to have a way of recording what has been dissolved in it, then perhaps, just perhaps, homeopathy is true and not just magical thinking.

So the premise is clear. The blog post is trying to sustain the lifeless, rotting corpse of homeopathy by giving it one final jolt of the metaphorical defibrillator in the hope that you don't have to go to the next room and give the relatives the bad news. So first off, let's establish that water is "weird".

Anyone who was listening in a basic secondary school science lesson can spot what is wrong with the next paragraph.

I know. That's not a fair question. She doesn't understand science in general. In fact, so many of her statements on science betray a distrust and dislike of science but she enjoys cloaking herself in it because it lends her nonsense a veneer of respectability. That's why Amazon puts her books in the science section and not the made up rubbish section where they belong.

As you'll see:

But all this stuff about water being odd is just the shaggy dog tale leading to this punchline:

If you missed the bit that isn't true, here it is again:

Be that as it may, McTaggart uses lasers as an analogy, some vague reference to other work and then:

And then Luc Montaignier. He won a Nobel for co-discovering the HIV virus. He went seriously woo, according to Orac. If his experiments did show that water can transmit information, they could be replicated. If anyone knows a genuine replication, I'd be interested. Orac points out the likely ways this is wrong, and I have no doubt many others point out some less likely ones.

Lynne McTaggart employs a lot of wishful thinking. Her intention experiments are wishful thinking wearing a comedy scientist outfit suitable for any children's fancy dress party. She wants homeopathy to be true. She wants water to have a memory. She wants all those evil scientists in their sinister labs cooking up nasty medicines to be wrong.

But she isn't a scientist and isn't steeped in the deeper and wider knowledge of science, its findings and its methods. As a result, she doesn't get one simple but extremely important point. If a new scientific finding is labelled controversial it is for a reason. That reason is that it asks too many areas of science to reconsider themselves. Scientists understand an incredibly substantial amount about the universe and those bits of information fit together in a tightly formed jigsaw puzzle. If someone comes along with a new piece that doesn't seem to fit and suggests that it just needs to be hammered in to place, there will inevitably be those that look more closely at the piece and suggest why it doesn't belong in the picture that is being built up.

Unless there is a lot of jiggling of the pieces we have in place already, the memory of water and the transmission of that memory will be put in the back of the drawer with the other discredited pieces.

Note: these are no links in McTaggart's piece. Nothing is referenced.

McTaggart has decided to take on water because it is the last refuge of the homeopath clinging to their discredited idea. If, and it is a pleading, longing, highly optimistic if, water can be found to have a way of recording what has been dissolved in it, then perhaps, just perhaps, homeopathy is true and not just magical thinking.

So the premise is clear. The blog post is trying to sustain the lifeless, rotting corpse of homeopathy by giving it one final jolt of the metaphorical defibrillator in the hope that you don't have to go to the next room and give the relatives the bad news. So first off, let's establish that water is "weird".

But we’re no closer to understanding exactly how water behaves. In fact, water drives most scientists crazy.Weird means anomalous in scientific language and scientists have a very good understanding of how those anomalous properties arise. Besides, anomalous is just compared to something else. Water is water, hydrogen sulfide is something else and they each have their own properties. Because water doesn't fit all the same patterns as we might have expected, does not make it weird. There is a good article on the anomalous properties of water here.

Water is a chemical anarchist, behaving like no other liquid in nature, displaying no less than 72 weird properties – and those are just what we’ve discovered thus far.

Anyone who was listening in a basic secondary school science lesson can spot what is wrong with the next paragraph.

Hot water behaves far differently than cold water; when water is heated, the molecules expand and it’s easy to compress, but when cooled they move more slowly, they shrink and they get harder to compressMolecules don't expand or contract. Thermal energy makes them move more rapidly (kinetic theory is called kinetic theory for a reason). Water has a diameter of about 2.75 angstrom (2.75 x 10e-10 metres). Molecules just don't expand or contract. Their increased movement produces the expansion. If that entirely basic and easily understood fact is beyond McTaggart, what chances are there that she can understand anything more complex?

I know. That's not a fair question. She doesn't understand science in general. In fact, so many of her statements on science betray a distrust and dislike of science but she enjoys cloaking herself in it because it lends her nonsense a veneer of respectability. That's why Amazon puts her books in the science section and not the made up rubbish section where they belong.

As you'll see:

Attempts to model water as the seemingly simple substance it is continue to fail. You could spend your entire career – and many scientists do – playing around with water and feel like you’re getting nowhere.So I Googled "Modelling behavior of water" and I got 1,660,000 hits in Google Scholar which seems to me quite a few and their titles suggest that a lot of progress has been made over the years and that modeling water has enabled us to understand an awful lot about water. You might note that I chose to search modeling behavior while McTaggart simply says modeling water. Her command of language also seems a bit weak on this post. The diagram below shows quite a lot about simple models of water that are, no doubt, above McTaggart's pay grade:

|

| From http://www.pnl.gov/science/images/highlights/cmsd/electron_models.jpg, about a paper modelling aspects of the bahaviour of water, how ironic. |

And now we’ve learned that water does two other special things that could change everything we think about how the world works: it stores information and also broadcasts it.And like all shaggy dog tales, there is something important to remember about them. Something about them isn't true.

If you missed the bit that isn't true, here it is again:

And now we’ve learned that water does two other special things that could change everything we think about how the world works: it stores information and also broadcasts it.The storage of information claim is based on the work of two Italian physicists:

Two Italian physicists at the Milan National Institute of Nuclear Research, the late Giuliano Preparata and his colleague the late Emilio Del Giudice, demonstrated mathematically that, when closely packed together, atoms and molecules exhibit collective behaviors and form what they termed 'coherent domains,’ much as a laser does.I will let Anna V in a comment on a physics forum explain quantum coherence, especially for Lynne McTaggart, who seems to think it is something magical:

Now coherence in quantum mechanics is due to the nature of the wave functions, which describe the underlying stratum of particles and molecules. These are sinusoidal functions which means they not only have an amplitude ( a measure) but also a phase. Coherence means that the phases of the wave function are kept constant between the coherent particles.Can't see information being stored there. Not in the sense that McTaggart will understand it.

Be that as it may, McTaggart uses lasers as an analogy, some vague reference to other work and then:

As other scientists went on to investigate, water molecules appear to become 'informed' in the presence of other molecules—that is, they tend to polarize around any charged molecule—storing and carrying its frequency so it can be read at a distance.Oh, dear. If it wasn't so poor so far, McTaggart has just nailed the flaw. A sentence that begins "This suggests..." does not get to be followed by one that begins "This means..." because a suggestion is not an assertion. It might be true, in which case the last sentence here should begin "If true, this means..." But it doesn't and less observant readers will miss the logical fallacy.

This suggests that water can act like a tape recorder, retaining and carrying information whether the original molecule is still there or not.

This means that water not only sends the signal but also amplifies it.

And then Luc Montaignier. He won a Nobel for co-discovering the HIV virus. He went seriously woo, according to Orac. If his experiments did show that water can transmit information, they could be replicated. If anyone knows a genuine replication, I'd be interested. Orac points out the likely ways this is wrong, and I have no doubt many others point out some less likely ones.

|

| Orac and friends |

Lynne McTaggart employs a lot of wishful thinking. Her intention experiments are wishful thinking wearing a comedy scientist outfit suitable for any children's fancy dress party. She wants homeopathy to be true. She wants water to have a memory. She wants all those evil scientists in their sinister labs cooking up nasty medicines to be wrong.

But she isn't a scientist and isn't steeped in the deeper and wider knowledge of science, its findings and its methods. As a result, she doesn't get one simple but extremely important point. If a new scientific finding is labelled controversial it is for a reason. That reason is that it asks too many areas of science to reconsider themselves. Scientists understand an incredibly substantial amount about the universe and those bits of information fit together in a tightly formed jigsaw puzzle. If someone comes along with a new piece that doesn't seem to fit and suggests that it just needs to be hammered in to place, there will inevitably be those that look more closely at the piece and suggest why it doesn't belong in the picture that is being built up.

Unless there is a lot of jiggling of the pieces we have in place already, the memory of water and the transmission of that memory will be put in the back of the drawer with the other discredited pieces.

Note: these are no links in McTaggart's piece. Nothing is referenced.

Monckton's pause hesitates again

I'm linking to an earlier post that gives the details but in brief, Lord Monckton has fudged his starting point for the non-pause in global warming yet again. Now he says February 1997. It might soon have to be February 2016 if some predictions for the current El Nino come true.

Full story at http://ingeniouspursuits.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/monckton-pauses-again-and-again-but.html

Full story at http://ingeniouspursuits.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/monckton-pauses-again-and-again-but.html

|

| Monckton when he was plain Christopher, from about the time he says the "pause" started (date unknown then) |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)